ChatGPT said:

Hello my friend! 😃

Let’s break it down. These int8, int16, int32, and int64 are signed integers, meaning they can represent both negative and positive numbers.

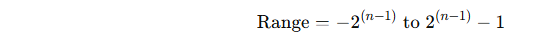

The value range is determined by the formula:

where n is the number of bits.

Value Scopes:

-

int8 (8-bit signed integer)

Range: −128 to 127 -

int16 (16-bit signed integer)

Range: −32,768 to 32,767 -

int32 (32-bit signed integer)

Range: −2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647 -

int64 (64-bit signed integer)

Range: −9,223,372,036,854,775,808 to 9,223,372,036,854,775,807

👉 If you meant unsigned integers (uint8, uint16, etc.), the ranges would instead be from 0 to 2^n − 1.

Do you want me to also list the unsigned ranges for completeness?

You said:

ChatGPT said:

Great question! 🚀 These three—float, double, and decimal—are all used to represent numbers with fractional parts, but they differ in precision, storage size, and use cases. Let’s break it down:

🔹 1. Float

-

Precision: ~7 decimal digits

-

Size: Usually 32 bits (4 bytes)

-

Storage: IEEE 754 single-precision floating point

-

Range: Approximately ±1.5 × 10^−45 to ±3.4 × 10^38

-

Use Case: Scientific calculations, graphics, situations where performance matters more than extreme precision.

-

⚠️ Issue: Rounding errors can happen (not exact for decimal fractions).

🔹 2. Double

-

Precision: ~15–16 decimal digits

-

Size: Usually 64 bits (8 bytes)

-

Storage: IEEE 754 double-precision floating point

-

Range: Approximately ±5.0 × 10^−324 to ±1.7 × 10^308

-

Use Case: Default for most scientific and engineering calculations where higher precision is needed.

-

⚠️ Still has rounding issues, though much smaller than

float.

🔹 3. Decimal

-

Precision: Up to 28–29 significant decimal digits

-

Size: Usually 128 bits (16 bytes)

-

Storage: Base-10 representation (not binary floating point)

-

Range: ±1.0 × 10^−28 to ±7.9 × 10^28 (much smaller range than float/double)

-

Use Case: Financial, monetary, or accounting calculations where exact decimal representation is critical (e.g., currency).

-

✅ Advantage: No binary rounding issues (e.g., 0.1 + 0.2 = 0.3 exactly).

-

❌ Slower performance and larger memory use compared to float/double.

⚖️ Quick Comparison Table

| Type | Size | Precision (digits) | Range (approx) | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| float | 4 bytes | ~7 | ±10^−45 → ±10^38 | Fast, scientific/graphics |

| double | 8 bytes | ~15–16 | ±10^−324 → ±10^308 | General-purpose high precision |

| decimal | 16 bytes | 28–29 | ±10^−28 → ±10^28 | Money, finance, exact decimals |

👉 Rule of thumb:

-

Use float/double for scientific/engineering.

-

Use decimal for financial/money values.

Would you like me to also show you examples in C# or Python to illustrate how they differ in practice (e.g., 0.1 + 0.2 issue)?

You said:

ChatGPT said:

Perfect 👍 Let’s test this in Python.

Python’s built-in float is actually a double-precision (64-bit) floating point.

For decimal you can use the decimal module.

Here’s a demo:

from decimal import Decimal, getcontext # set decimal precision high enough getcontext().prec = 30 # Float (binary floating point) a = 0.1 + 0.2 print("float 0.1 + 0.2 =", a) # Not exactly 0.3 print("float equals 0.3 ?", a == 0.3) # Decimal (exact decimal arithmetic) b = Decimal("0.1") + Decimal("0.2") print("decimal 0.1 + 0.2 =", b) # Exactly 0.3 print("decimal equals 0.3 ?", b == Decimal("0.3"))

🔎 Output:

float 0.1 + 0.2 = 0.30000000000000004 float equals 0.3 ? False decimal 0.1 + 0.2 = 0.3 decimal equals 0.3 ? True

✅ Why this happens:

-

float(anddouble) store numbers in binary fractions, so0.1and0.2can’t be represented exactly. -

Decimalstores numbers as base-10 fractions, so0.1is exact.

Do you also want me to show how numpy.float32 (float) differs from Python’s built-in float (double) in precision?

You said:

ChatGPT said:

Great! 😃 Let’s dive into numpy.float32 vs Python float (which is float64).

Python’s built-in float is a C double (64-bit).

NumPy gives you float32 (single precision, ~7 digits) and float64 (double precision, ~15–16 digits).

Here’s a demo:

import numpy as np # Float32 (single precision) a32 = np.float32(0.1) + np.float32(0.2) print("np.float32 0.1 + 0.2 =", a32) print("Equals 0.3 ?", a32 == np.float32(0.3)) # Float64 (double precision) - same as Python float a64 = np.float64(0.1) + np.float64(0.2) print("np.float64 0.1 + 0.2 =", a64) print("Equals 0.3 ?", a64 == np.float64(0.3)) # Python built-in float py_float = 0.1 + 0.2 print("Python float 0.1 + 0.2 =", py_float) print("Equals 0.3 ?", py_float == 0.3)

🔎 Typical Output:

np.float32 0.1 + 0.2 = 0.30000001 Equals 0.3 ? False np.float64 0.1 + 0.2 = 0.30000000000000004 Equals 0.3 ? False Python float 0.1 + 0.2 = 0.30000000000000004 Equals 0.3 ? False

✅ Key takeaways:

-

np.float32is less precise → you see0.30000001. -

np.float64and Python float are the same (double precision) →0.30000000000000004. -

Both have binary rounding issues, but

float32is worse because it only keeps ~7 significant digits.

ChatGPT said:

Good question 👍

In NumPy, numpy.nan is a special constant representing “Not a Number” (like IEEE 754 NaN).

🔎 Its data type:

import numpy as np print(type(np.nan)) # Python type print(np.nan.dtype) # NumPy dtype (will raise error!)

Output:

<class 'float'> AttributeError: 'float' object has no attribute 'dtype'

👉 So np.nan is actually a Python float (specifically, a float('nan')).

That means it has the type:

-

Python type:

<class 'float'> -

NumPy dtype (when inside arrays): depends on the array’s dtype (e.g.,

float32,float64).

Example with arrays:

arr64 = np.array([1.0, np.nan], dtype=np.float64) print(arr64.dtype) # float64 arr32 = np.array([1.0, np.nan], dtype=np.float32) print(arr32.dtype) # float32

✅ So:

-

np.nanitself is a Python float (64-bit). -

Inside NumPy arrays, it adapts to the array’s dtype (e.g.,

float32nan,float64nan).

Would you like me to also explain how np.nan differs from None in NumPy?

You said:

ChatGPT said:

Awesome 👍 Let’s carefully compare np.nan vs None in NumPy, because they behave very differently.

🔹 1. np.nan

-

Meaning: “Not a Number” (IEEE 754 NaN).

-

Type: A Python float (

<class 'float'>). -

NumPy behavior: Can only live in floating-point dtypes (

float32,float64). -

Math operations: Still allowed, but results propagate NaNs.

import numpy as np x = np.array([1.0, np.nan, 3.0]) print(x.dtype) # float64 print(np.mean(x)) # nan (NaN propagates) print(np.isnan(np.nan)) # True

🔹 2. None

-

Meaning: Python’s null object (absence of value).

-

Type:

<class 'NoneType'>. -

NumPy behavior: If you put

Nonein a NumPy array:-

If all elements are numeric → NumPy upcasts to object dtype.

-

It cannot live in pure numeric dtypes.

-

y = np.array([1.0, None, 3.0]) print(y.dtype) # object print(y) # [1.0 None 3.0]

-

Math operations: Fail, because

Noneis not numeric.

print(np.mean(y)) # TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'float' and 'NoneType'

🔎 Key Differences

| Feature | np.nan | None |

|---|---|---|

| Python type | float |

NoneType |

| NumPy dtype | float32/float64 |

Forces array to object |

| Math ops | Work but yield nan |

Not supported (errors) |

| Use case | Missing/invalid numeric | General “no value” placeholder |

👉 Rule of thumb:

-

Use

np.nanfor missing numeric data. -

Use

Noneonly when working with object arrays or non-numeric data.

Do you want me to also cover how np.nan interacts with pd.NA and pd.NaT in pandas (since missing values get more nuanced there)?

You said:

ChatGPT said:

Perfect — this is where things get interesting because pandas extends NumPy’s ideas of “missing values.” Let’s break down np.nan, pd.NA, and pd.NaT. 🚀

🔹 1. np.nan

-

From NumPy, a

float('nan'). -

Type:

<class 'float'>. -

Pandas behavior: Used historically to represent missing values in numeric columns.

-

Still common, but has quirks:

-

np.nan == np.nanis alwaysFalse. -

isna()detects it.

-

import numpy as np import pandas as pd s = pd.Series([1, np.nan, 3]) print(s) print(s.isna()) # Detects np.nan as missing

🔹 2. pd.NA

-

Introduced in pandas 1.0+ as a generic missing value marker.

-

Type:

<class 'pandas._libs.missing.NAType'>. -

Works across numeric, boolean, string, categorical dtypes (with new “nullable” dtypes like

Int64,boolean,string). -

Unlike

np.nan, comparisons returnpd.NAinstead ofFalse(propagates missingness).

s = pd.Series([1, pd.NA, 3], dtype="Int64") print(s) print(s.isna()) # Detects pd.NA print(pd.NA == pd.NA) # Returns pd.NA (not True/False)

🔹 3. pd.NaT

-

Special case of

NaT= Not a Time. -

For datetime and timedelta dtypes.

-

Type:

<class 'pandas._libs.tslibs.nattype.NaTType'>.

s = pd.Series([pd.Timestamp("2023-01-01"), pd.NaT]) print(s) print(s.isna()) # Detects NaT

🔎 Summary Table

| Value | Library | Type | Use case | Comparison behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|

np.nan |

NumPy | float |

Missing numeric values (legacy in pandas) | np.nan == np.nan → False |

pd.NA |

pandas | NAType |

General missing marker for new dtypes | pd.NA == pd.NA → pd.NA |

pd.NaT |

pandas | NaTType |

Missing datetime/timedelta values | pd.NaT == pd.NaT → False |

👉 Rule of thumb in pandas:

-

Use

pd.NAfor new code (especially with nullable dtypes). -

Use

pd.NaTfor datetime-like data. -

np.nanis still common in older code and when working directly with NumPy.

浙公网安备 33010602011771号

浙公网安备 33010602011771号