关于数学的结构 -> 等价问题,函数的研究

On the Structure of Mathematics

If you look at articles in current journals, the range of topics seems immense. How could anyone even begin to make sense out of all of these topics? And indeed there is a glimmer of truth in this. People cannot effortlessly switch from one research field to another. But not all is chaos. There are at least two ways of placing some type of structure on all of mathematics.

Equivalence Problems

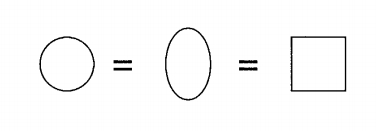

Mathematicians want to know when things are the same, or, when they are equivalent. What is meant by "the same" is what distinguishes one branch of mathematics from another. For example, a topologist will consider two geometric objects (technically, two topological spaces) to be the same if one can be twisted and bent, but not ripped, into the other. Thus for a topologist, we have:

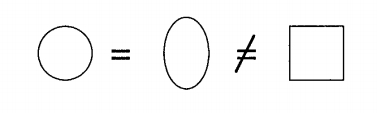

To a differential topologist, two geometric objects are the same if one can be smoothly bent and twisted into the other. By smooth, we mean that no sharp edges can be introduced. Then:

The four sharp corners of the square are what prevent it from being equivalent to the circle.

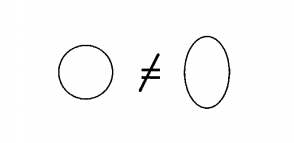

For a differential geometer, the notion of equivalence is even more restrictive. Here two objects are the same not only if one can be smoothly bent and twisted into the other but also if the curvatures agree. Thus for the differential geometer, the circle is no longer equivalent to the ellipse:

As a first pass to placing structure on mathematics, we can view an area of mathematics as consisting of certain objects, coupled with the notion of equivalence between these objects. We can explain equivalence by looking at the allowed maps, or functions, between the objects. At the beginning of most chapters, we will list the objects and the maps between the objects that are key for that subject. The equivalence problem is, of course, the problem of determining when two objects are the same, using the allowable maps.(所以这本书中,作者在每一个chapter的开头都会列出Basic Object, Basic Map )

If the equivalence problem is easy to solve for some class of objects, then the corresponding branch of mathematics will no longer be active. If the equivalence problem is too hard to solve, with no known ways of attacking the problem, then the corresponding branch of mathematics will again not be active, though of course for opposite reasons. The hot areas of mathematics are precisely those for which there are rich partial but not complete answers to the equivalence problem. But what could we mean by a partial answer?

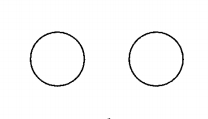

Here enters the notion of invariance. Start with an example. Certainly, the circle, as a topological space, is different from two circles:

since a circle has only one connected component and two circles have two connected components. We map each topological space to a positive integer, namely the number of connected components of the topological space. Thus we have:

The key is that the number of connected components for a space cannot change under the notion of topological equivalence (under bendings and twistings). We say that the number of connected components is an invariant of a topological space. Thus, if the spaces map to different numbers, meaning that they have different numbers of connected components, then the two spaces cannot be topologically equivalent.

Of course, two spaces can have the same number of connected components and still be different. For example, both the circle and the sphere

have only one connected component, but they are different. (These can be distinguished by looking at each space's dimension, which is another topological invariant.) The goal of topology is to find enough invariants to be able to always determine when two spaces are different or the same. This has not come close to being done.(这一目标尚未接近完成。) Much of algebraic topology maps each space not to invariant numbers but to other types of algebraic objects, such as groups and rings. Similar techniques show up throughout mathematics. This provides for tremendous interplay between different branches of mathematics.

The Study of Functions

The mantra that we should all chant each night before bed is:

"Functions describe the World."

To a large extent, what makes mathematics so useful to the world is that seemingly disparate real-world situations can be described by the same type of function. For example, think of how many different problems can be recast as finding the maximum or minimum of a function.

Different areas of mathematics study different types of functions. Calculus studies differentiable functions from the real numbers to the real numbers, algebra studies polynomials of degree one and two (in high school) and permutations (in college), linear algebra studies linear functions, or matrix multiplication.

Thus, in learning a new area of mathematics, you should always "find the function" of interest. Hence, at the beginning of most chapters, we will state the type of function that will be studied.

Equivalence Problems in Physics

Physics is an experimental science. Hence, any question in physics must eventually be answered by performing an experiment. But experiments come down to making observations, which usually are described by certain computable numbers, such as velocity, mass, or charge. Thus, the experiments in physics are described by numbers that are read off in the lab. More succinctly, physics is ultimately:

"Numbers in Boxes"

where the boxes are various pieces of lab machinery used to make measurements. But different boxes (different lab set-ups) can yield different numbers, even if the underlying physics is the same. This happens even at the trivial level of choice of units.

More deeply, suppose you are modeling the physical state of a system as the solution of a differential equation. To write down the differential equation, a coordinate system must be chosen. The allowed changes of coordinates are determined by the physics. For example, Newtonian physics can be distinguished from Special Relativity in that each has different allowable changes of coordinates.

Thus, while physics is "Numbers in Boxes," the true questions come down to when different numbers represent the same physics. But this is an equivalence problem; mathematics comes to the fore. (This explains in part the heavy need for advanced mathematics in physics.) Physicists want to find physics invariants. Usually, though, physicists call their invariants "Conservation Laws." For example, in classical physics, the conservation of energy can be recast as the statement that the function that represents energy is an invariant function.

Reference

All the Mathematics You Missed But Need to Know for Graduate School

浙公网安备 33010602011771号

浙公网安备 33010602011771号