SDSU Sage Tutorial v1.1学习笔记

and Sage universes and coercion

The final part, Mathematical Structures, introduces the reader to topics that one finds in a college level curriculum: linear algebra, number theory, groups, rings, fields, etc. Another important universe is the Symbolic Ring.

You might think that  or

or  would have parent RR, the real numbers, while

would have parent RR, the real numbers, while  would be in CC. But RR and CC have finite precision, and these numbers satisfy formulas that make them special, for example

would be in CC. But RR and CC have finite precision, and these numbers satisfy formulas that make them special, for example  and

and  . The Symbolic Ring is where Sage stores these numbers with special properties.

. The Symbolic Ring is where Sage stores these numbers with special properties.

sage: sin(pi)

0

sage: sin(pi.n())

1.22464679914735e-16

sage: sin(pi/10)

1/4*sqrt(5) - 1/4

sage: cos(pi/5)

1/4*sqrt(5) + 1/4

sage: sin(5*pi/12)

1/12*(sqrt(3) + 3)*sqrt(6)

sage: log(100,10)

2

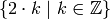

A particularly useful technique in python (and Sage by extension) is the construction of lists using list comprehensions. This feature is very similar to the set builder notation we often use in mathematics. For example, the set of even integers can be written as:

Where we do not explicitly list the elements of the set but rather give a rule which can used to construct the set. We can do something very similar in python by placing a for inside of a list, like in the following example. Here is how we would construct the list of even integers from  to

to  .

.

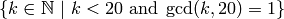

We can also use the list comprehension filter (or reduce) the results by adding a conditional to our list comprehension. For example, to construct the list of all natural numbers that are less than  which are relatively prime to 20 we do the following:

which are relatively prime to 20 we do the following:

sage: [ k for k in [1..19] if gcd(k,20) ==

1 ]

[1, 3, 7, 9, 11, 13, 17, 19]

Notice that the syntax for the construction is nearly identical to the mathematical way that we would write the same set of numbers:

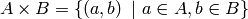

In mathematics we often construct the Cartesian Product of two sets:

We can do something similar by using multiple for's in the list comprehension. For example, to construct the list of all pairs of elements in the list constructed earlier we do the following:

sage: U = [ k for k in [1..19] if gcd(k,20) ==

1]

sage: [ (a,b) for a in U for b in U ]

[(1, 1), (1, 3), (1, 7), (1, 9), (1, 11), (1, 13), (1, 17), (1, 19), (3, 1), (3, 3), (3, 7), (3, 9), (3, 11), (3, 13), (3, 17), (3, 19), (7, 1), (7, 3), (7, 7), (7, 9), (7, 11), (7, 13), (7, 17), (7, 19), (9, 1), (9, 3), (9, 7), (9, 9), (9, 11), (9, 13), (9, 17), (9, 19), (11, 1), (11, 3), (11, 7), (11, 9), (11, 11), (11, 13), (11, 17), (11, 19), (13, 1), (13, 3), (13, 7), (13, 9), (13, 11), (13, 13), (13, 17), (13, 19), (17, 1), (17, 3), (17, 7), (17, 9), (17, 11), (17, 13), (17, 17), (17, 19), (19, 1), (19, 3), (19, 7), (19, 9), (19, 11), (19, 13), (19, 17), (19, 19)]

It should be noted that I didn't only have to form tuples of the pairs of elements. I can also find the product or the sum of them. Any valid expression involving a and b will be fine.

In this section we cover how to construct  , the ring of integers modulo

, the ring of integers modulo  , and do some basic computations.

, and do some basic computations.

To construct  you use the Integers command.

you use the Integers command.

sage: Integers(7)

Ring of integers modulo 7

sage: Integers(100)

Ring of integers modulo 100

We could do computations modulo an integer by repeatedly using the % operator in all of our expressions, but by constructing the ring explicitly we have access to a more natural method for doing arithmetic.

sage: R=Integers(13)

sage: a=R(6)

sage: b=R(5)

sage: a + b

11

sage: a*b

4

And by explicitly coercing our numbers into the ring  we can compute some of the mathematical properties of the elements. Like their order, both multiplicative and additive, and whether or not the element is a unit.

we can compute some of the mathematical properties of the elements. Like their order, both multiplicative and additive, and whether or not the element is a unit.

sage: a.additive_order()

13

sage: a.multiplicative_order()

12

sage: a.is_unit()

True

sage: R=Integers(13)

sage: a=R(6)

sage: b=R(5)

sage: a + b

11

sage: a*b

4

Of course, if all we want is the echelon form of the matrix we can use either the echelon_form() or echelonize() methods. The difference between the two is the former returns a copy of the matrix in echelon form without changing the original matrix and the latter alters the matrix itself.

Polynomial Rings

Constructing polynomial rings in Sage is fairly straightforward. We just specify the name of the "indeterminate" variable as well as the coefficient ring.

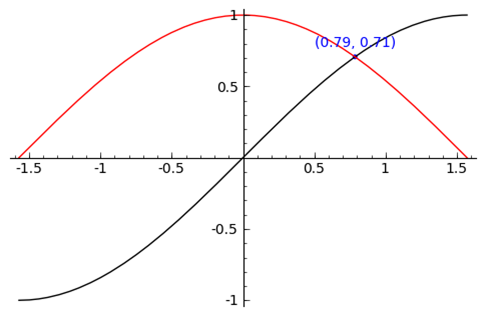

sage: find_root( sin(x) == cos(x),-pi/2, pi/2 )

0.78539816339744839

sage: P = point( [(0.78539816339744839, sin(0.78539816339744839))] )

sage: T = text("(0.79,0.71)", (0.78539816339744839, sin(0.78539816339744839) +

.10))

sage: s = P + r + T

sage: s.show()

浙公网安备 33010602011771号

浙公网安备 33010602011771号