【文献综述】行为经济学前景介绍

A perspective on psychology and economics(Matthew Rabin 2002)

More psychological realism

Traditional mainstream assumptions

People:

- are Bayesian information processors;

- have well-defined and stable preferences;

- maximize their expected utility;

- exponentially discount future well-being;

- are self-interested ; narrowly defined;

- have preferences over final outcomes; not changes;

- have only “instrumental”/functional taste for beliefs and information. (beliefs and information won't change utility.)

Classic choice model:

where \(X\) is choice set, \(S\) is state space, \(\pi(s)\) are the person’s subjective beliefs updated using Bayes’ Rule, and \(U\) are stable, well-defined preferences.

Three categories of psychological phenomena:

- New assumptions about preferences – what does \(U(x|s)\) really look like?

- Heuristics and biases in judgment – how do people really form beliefs \(p(s) \neq\pi(s)\)?

- Lack of “stable utility maximization” – do people really \(\max \limits_{x\in X} \sum \limits_{s \in S} \pi (s) U(x|s)\)?

Caring about changes

Changes about certain references rather than solely absolute levels matter.

-

Reference-based preference

- Loss aversion

Endowment effect: the fact that people who have randomly been given virtually any object will instantly value the object more than those who have not been endowed with the object.

- Incorporate reference-independence into utility theory: \(U(c) \rightarrow U(c,r)\), where \(c\) denotes a certain consuming level, \(r\) indicates the reference.

-

Two frictions to incorporate reference levels in determining preference

- The role of changes is not fully recognized

Potential direction: welfare effects of individual income and national growth with central attention to the possibility that increases in consumption may not bring lasting increases in satisfaction to the individuals involved. Chinese GDP's growth rate compares to my income's growth rate.

-

Attitudes towards losses and other changes cannot fully interpreted in utility-maximization terms

- People probably over-react to changes, especially losses. Two notable explanations:

- People exaggerate how long sensations of gains and losses will last.

- We isolate particular experiences and decisions from each other.

-

Risk aversion

Consider a small stake (50%, $110; 50%, $100) gamble.

- Classic explanation: \(U''(w)<0\), diminishing marginal utility. However, the classical expected-utility predicts risk neutrality over non-huge stakes, which is counter-factual. Samuelson's colleague.

Assume person has a diminishing marginal utility function decided by his/her wealth \(U(w)=ln(w)\). According to expected-utility theory, if

he/she would like to join the gamble. The condition is equivalent to \(w>1100\). It is not a severe condition, however, few people are willing to take part in it.

Behavioral economics explanation: Our attitudes towards risk are driven primarily by attitudes towards change in wealth levels.

Caring about others

- Altruism

- People care more about the fairness of the distribution of resources than their own direct well-being.

- People care about intentions and motives, and want to reciprocate the good or bad behavior of others.

Circumstance matters: Players in games behave systematically differently as a function of previous behavior by other players. This shows that people care not just about outcomes, but also how they arrived at those outcomes.

Self interest and economics

- Ultimatum game puzzle: An experimental subject sacrificing (say) $8 to punish an unfair ($92, $8) offer.

- A movie analogy -- The Road Retaliator

Caring about now

- Classic model: Exponential discount

- Counter-factual property: The functional form generates time-consistent preferences.

- Psychology point, which is also common sense, is that people have present-biased preferences.

- A person discounts near-term incremental delays in well-being more severely than she discounts distant-future incremental delays.

- Formal model

Let \(U^{\tau}\) be "intertemporal preferences" which indicates the preferences at the moment \(\tau\) and let \(u_t\) be instantaneous utilities.

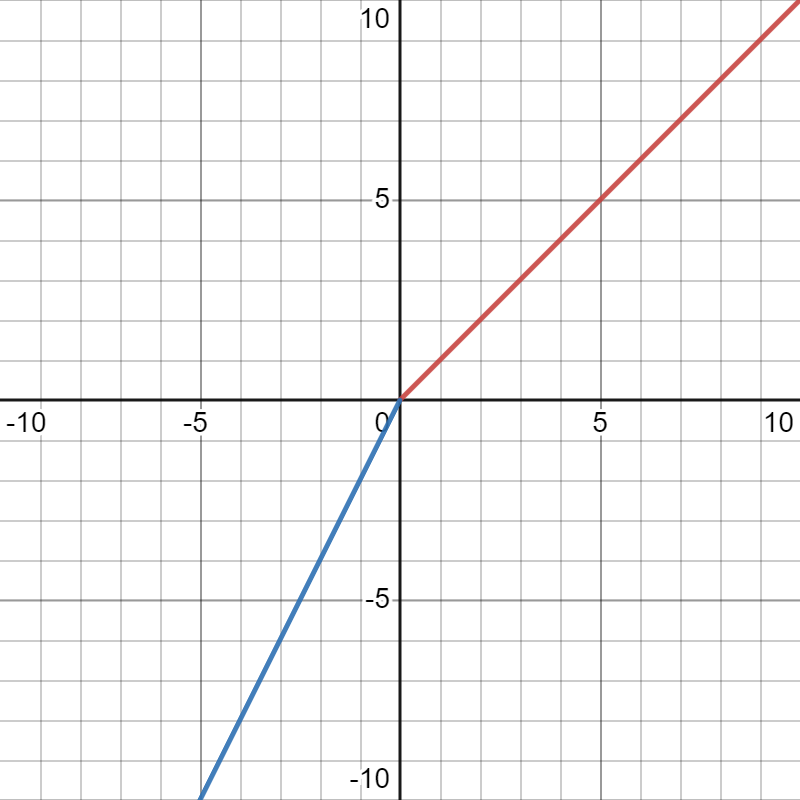

- Exponential discounting: \(U^{\tau} = \int_{t= \tau}^T e^{-r(t-\tau)}u_t\). More information about continuous discount.

- Hyperbolic discounting: \(U^{\tau} = \int_{t= \tau}^T \dfrac{1}{(t-\tau)+k}u_t\).

- Discrete-time discounting: \(U^{\tau}(u_t,u_{t+1},\dots,u_{T})\equiv(\delta)^tu_t+\beta\sum\limits_{\tau =t+1}^T(\delta)^{\tau}u_t\).

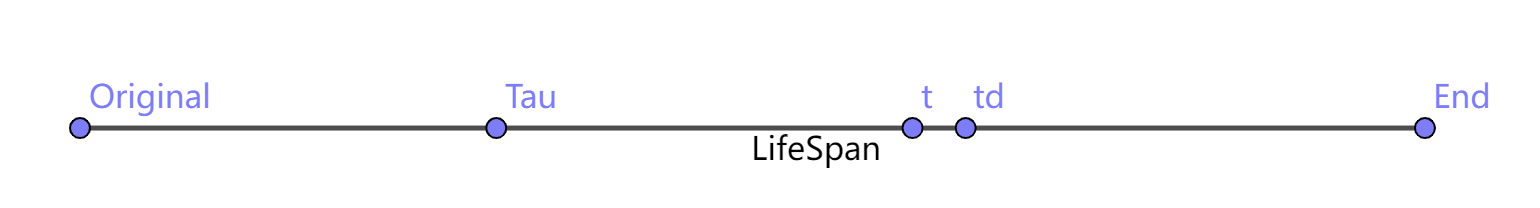

The graph above gives a visual explanation of intertemporal preference. "Original" and "End" points denote the begin and end of the person's life separately. The "Tau" point illustrates the very moment person perceives his/her preference over the period from "Tau" to "End". Every single moment in this period has its certain instantaneous utility and the discounting rate to the "Tau" point. Now, consider a moment "t" in this period, and the moment "td" represents the moment follows "t" with such a small constant time period \(d\) that the instantaneous utilities stain unchanged during period \(d\). Then I want to figure out whether the discounting rate over the certain period time \(d\) changes along with "t" under different kinds of discounting models. I only consider exponential discounting and hyperbolic discounting.

1.Exponential discounting

Suppose the discounting rate over \(d\) is \(\delta_{t,d}\), which is defined that concerning about both \(t\) and \(d\). It is obvious that the discounting utility at the moment "Tau" of the instantaneous utility at the moment "td" could be treated as two-parts discounting process, say first discounted from "td" to "t" and then from "t" to "Tau". Therefore, it is same to say $\delta_{t,d} \delta_t=\delta_{t+d} $, hence \(\delta_{t,d}=\dfrac{\delta_{t+d}}{ \delta_t}\).

Under exponential discounting model, we have \(\delta_t^{\tau} = e^{-r(t-\tau)}\), therefore \(\delta_{t,d}=\dfrac{\delta_{t+d}}{ \delta_t} = \dfrac{e^{-r(t+d-\tau)}}{e^{-r(t-\tau)}}=e^{-rd}\). The result shows that the discounting rate over the certain distant period \(d\) remain constant no matter where the moment "t" is. Hence, the person has a **time-consistency **preference.

2.hyperbolic discounting

However, under hyperbolic discounting moder, we have \(\delta_t^{\tau} = \dfrac{1}{(t-\tau)+k}\), therefore \(\delta_{t,d}=\dfrac{\delta_{t+d}}{ \delta_t} = \dfrac{t-\tau+k}{t+d-\tau+k}=\dfrac{1}{1+\frac{d}{t-\tau+k}}\). In this occasion, the discounting rate over the period \(d\) of same distance also changes with the moment "t", as the formula shows that, the closer the moment "t" is to the moment "Tau", it is the same to say the smaller the \(t\), the smaller the discounting factor, it is the same to say the big the utility discounted from "td" to "t". The result shows that the patience of the person decreases while the "t" getting closer to "Tau". So, he/she has a present-biased preference. I also once wrote an article by using Python program to simulate different kinds of discounting models to demonstrate a time inconsistence preference.

- Superiority of the present-biased model

- The present-biased preference is very common.

- As a explanation for delaying gratification aversion, exponential discounting is miscalibrated.

If we use exponential discounting to explain people's procrastination, the result is ridiculous. Actually the exponential discounting is a theory of complete short-term patience. Any degree of short-term impatience that shows up on the radar screen implies ridiculous long-term impatience - if you cram it in the exponential-discounting framework.

Themes and perspectives

Psychological economics and mainstream economics

- There are trade-offs in human psychological nature and model simplification.

- Then the author drew a Big pancake to show that psychological economics has a great perspective.

Cautions and worries

- Overly reception to alternative assumptions that have no better grounded psychological reality.

- Bear in mind the purpose of merging psychology and economics is to capture realistic and economically important aspects of human nature.

- No simple generalization about some facet of human behavior is literally true should not prevent us from attempting to develop stylized, tractable models that aid us in economic insight.

Some common objections

- Economists worry that, if we allow new assumptions, then researchers could come along and assume anything. "We Can't Consider All Alternatives".

- Argument: Psychological assumptions are not randomly proposed and seem to be behaviorally true in experiment and reality.

- Resistance from methodology. "If it ain't broke, don't fix it".

- Argument: Our tastes are not completely well-defined, stable, and coherent, and the departures appear not to be economically negligible.

- "Markets will wipe [any unfamiliar psychological phenomenon] out".

- Argument: First, the markets negating departures is striking. What's more, even if highly competitive asset market do wipe out the influence of psychological phenomena, we should still not ignore the psychological phenomena for three reasons:

- Financial economists often care only about approximate market prices and neglect the irrational individuals and the allocation achieved.

- Not all economic behavior is mediated by frictionless, Walrasian markets. Perfect competition is manifestly not the sole environment of interest.

- Ignoring psychological phenomena doesn't manifest itself in competitive markets.

- Argument: First, the markets negating departures is striking. What's more, even if highly competitive asset market do wipe out the influence of psychological phenomena, we should still not ignore the psychological phenomena for three reasons:

At the movies: Economics from another planet

- Assumed planet: Planet Nonhollywood

- The actual economy developed exactly has it has here on Earth.

- Economists: Things that could not be eaten, touched, pushed, etc., and especially that were temporary, were simply not a direct part of anybody's utility function.

- Psychologists talked all the time about such phenomena, but economists dismissed them as woolly-headed and unscientific.

- Whether people intrinsically value movies?

- There are alternative "standard" explanations: go to theater for food; go to theater for money under the seats; go to theater as a signal of wealth by wasting money ... ...

- The alleged "preference" (like movies) is "unstable"

- Evidence shows people learn they don't like movies: people won't spend money on the same movie repeatedly ... ...

- ... ...

- Back on earth

- People have intrinsic taste for fairness and other non-self-interested preferences.

- Do those who reject money in the ultimatum game really get nothing?

- For those interested in economic outcomes, it will be more sensible to assume that people are willing to spend money on whatever they are willing to spend money on.

浙公网安备 33010602011771号

浙公网安备 33010602011771号