25-1 派生对象对基类的指针与引用

在上一章中,你已经全面掌握了如何利用继承从现有类派生出新类。本章我们将聚焦于继承最关键且强大的特性之一——虚函数。

但在探讨虚函数的本质之前,让我们先厘清其存在的必要性。

在24.3节 派生类的构造顺序章节中,你了解到创建派生类时,它由多个部分组成:每个继承类各占一部分,自身再占一部分。

例如,以下是一个简单案例:

#include <string_view>

class Base

{

protected:

int m_value {};

public:

Base(int value)

: m_value{ value }

{

}

std::string_view getName() const { return "Base"; }

int getValue() const { return m_value; }

};

class Derived: public Base

{

public:

Derived(int value)

: Base{ value }

{

}

std::string_view getName() const { return "Derived"; }

int getValueDoubled() const { return m_value * 2; }

};

当我们创建一个派生对象时,它包含一个基类部分(首先构造)和一个派生类部分(其次构造)。请记住,继承意味着两个类之间存在一种“是”关系。由于派生类是基类,因此派生类包含基类部分是恰当的。

指针、引用和派生类

我们能够将派生类的指针和引用指向派生类对象,这应该相当直观:

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

Derived derived{ 5 };

std::cout << "derived is a " << derived.getName() << " and has value " << derived.getValue() << '\n';

Derived& rDerived{ derived };

std::cout << "rDerived is a " << rDerived.getName() << " and has value " << rDerived.getValue() << '\n';

Derived* pDerived{ &derived };

std::cout << "pDerived is a " << pDerived->getName() << " and has value " << pDerived->getValue() << '\n';

return 0;

}

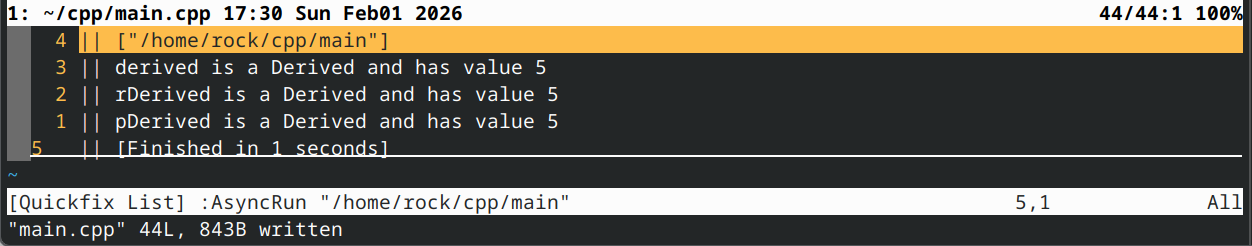

这将产生以下输出:

然而,由于派生类具有基类部分,一个更有趣的问题是:C++是否允许我们将指向基类的指针或引用赋值给派生类对象?事实证明,我们可以做到!

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

Derived derived{ 5 };

// These are both legal!

Base& rBase{ derived }; // rBase is an lvalue reference (not an rvalue reference)

Base* pBase{ &derived };

std::cout << "derived is a " << derived.getName() << " and has value " << derived.getValue() << '\n';

std::cout << "rBase is a " << rBase.getName() << " and has value " << rBase.getValue() << '\n';

std::cout << "pBase is a " << pBase->getName() << " and has value " << pBase->getValue() << '\n';

return 0;

}

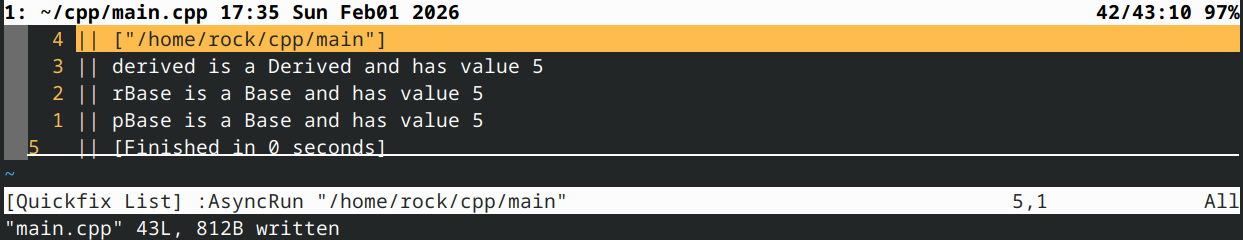

这产生了以下结果:

这个结果可能与你最初的预期不尽相同!

原来由于 rBase 和 pBase 分别是 Base 的引用和指针,它们只能访问 Base 的成员(或 Base 继承的任何类)。因此,尽管 Derived::getName() 会遮蔽(隐藏)Derived 对象的 Base::getName(),但 Base 指针/引用无法访问 Derived::getName()。因此它们调用的是 Base::getName(),这正是 rBase 和 pBase 报告自身类型为 Base 而非 Derived 的原因。

请注意,这也意味着无法通过 rBase 或 pBase 调用 Derived::getValueDoubled()——它们完全无法访问 Derived 的成员。

下面是另一个稍复杂的示例,我们将在下一课中进一步展开:

#include <iostream>

#include <string_view>

#include <string>

class Animal

{

protected:

std::string m_name;

// We're making this constructor protected because

// we don't want people creating Animal objects directly,

// but we still want derived classes to be able to use it.

Animal(std::string_view name)

: m_name{ name }

{

}

// To prevent slicing (covered later)

Animal(const Animal&) = delete;

Animal& operator=(const Animal&) = delete;

public:

std::string_view getName() const { return m_name; }

std::string_view speak() const { return "???"; }

};

class Cat: public Animal

{

public:

Cat(std::string_view name)

: Animal{ name }

{

}

std::string_view speak() const { return "Meow"; }

};

class Dog: public Animal

{

public:

Dog(std::string_view name)

: Animal{ name }

{

}

std::string_view speak() const { return "Woof"; }

};

int main()

{

const Cat cat{ "Fred" };

std::cout << "cat is named " << cat.getName() << ", and it says " << cat.speak() << '\n';

const Dog dog{ "Garbo" };

std::cout << "dog is named " << dog.getName() << ", and it says " << dog.speak() << '\n';

const Animal* pAnimal{ &cat };

std::cout << "pAnimal is named " << pAnimal->getName() << ", and it says " << pAnimal->speak() << '\n';

pAnimal = &dog;

std::cout << "pAnimal is named " << pAnimal->getName() << ", and it says " << pAnimal->speak() << '\n';

return 0;

}

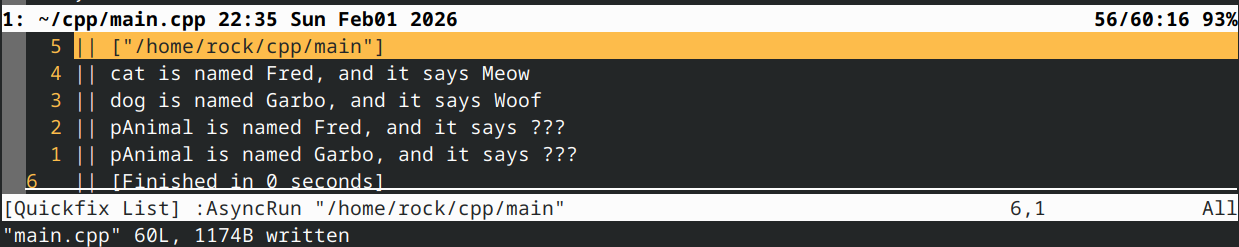

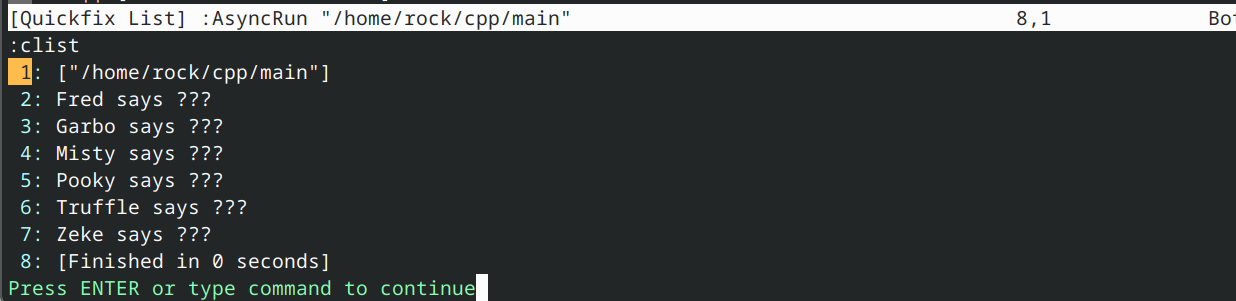

这产生了以下结果:

我们在这里遇到了相同的问题。由于 pAnimal 是 Animal 类型的指针,它只能访问该类的 Animal 部分。因此,pAnimal->speak() 调用的是 Animal::speak() 函数,而非 Dog::Speak() 或 Cat::speak() 函数。

用于基类的指针和引用

此刻你或许会说:“上述示例似乎有些荒谬。既然可以直接使用派生对象,为何还要为派生对象设置指向基类的指针或引用?”事实上,这背后存在诸多合理原因。

首先,假设你想编写一个函数来打印动物的名称和叫声。若不使用基类指针,你必须通过重载函数实现,例如:

void report(const Cat& cat)

{

std::cout << cat.getName() << " says " << cat.speak() << '\n';

}

void report(const Dog& dog)

{

std::cout << dog.getName() << " says " << dog.speak() << '\n';

}

难度不大,但试想如果动物类型从2种增加到30种会怎样?你得编写30个几乎完全相同的函数!更何况,每当新增一种动物类型时,还得为其单独编写新函数。考虑到真正的差异仅在于参数类型,这简直是巨大的时间浪费。

然而,由于猫和狗都继承自动物类,它们都具备动物的特性。因此,我们完全可以这样做:

void report(const Animal& rAnimal)

{

std::cout << rAnimal.getName() << " says " << rAnimal.speak() << '\n';

}

这将使我们能够传递任何从Animal派生的类,甚至包括我们在编写函数后创建的类!我们不再需要为每个派生类编写独立函数,而是获得一个适用于所有从Animal派生类的通用函数!

问题在于,由于rAnimal是Animal的引用,调用rAnimal.speak()时将调用Animal::speak(),而非派生类的speak()方法。

顺带一提……:

我们也可以使用模板函数来减少需要编写的重载函数数量:template <typename T> void report(const T& rAnimal) { std::cout << rAnimal.getName() << " says " << rAnimal.speak() << '\n'; }虽然这种方法可行,但存在自身问题:

- 无法确定类型T的具体含义,因为我们已丢失T应为Animal类型的注释说明。

- 该函数并未强制要求T必须是Animal类型。相反,它会接受任何包含getName()和speak()成员函数的对象类型,无论这种类型组合是否合理。

其次,假设你有3只猫和3只狗,想用数组存储以便快速访问。由于数组只能容纳单一类型的对象,且没有指向基类的指针或引用,你必须为每个派生类型创建不同的数组,如下所示:

#include <array>

#include <iostream>

// Cat and Dog from the example above

int main()

{

const auto& cats{ std::to_array<Cat>({{ "Fred" }, { "Misty" }, { "Zeke" }}) };

const auto& dogs{ std::to_array<Dog>({{ "Garbo" }, { "Pooky" }, { "Truffle" }}) };

// Before C++20

// const std::array<Cat, 3> cats{{ { "Fred" }, { "Misty" }, { "Zeke" } }};

// const std::array<Dog, 3> dogs{{ { "Garbo" }, { "Pooky" }, { "Truffle" } }};

for (const auto& cat : cats)

{

std::cout << cat.getName() << " says " << cat.speak() << '\n';

}

for (const auto& dog : dogs)

{

std::cout << dog.getName() << " says " << dog.speak() << '\n';

}

return 0;

}

现在,设想一下如果你有30种不同的动物会怎样。你需要30个数组,每种动物对应一个数组!

然而,由于猫和狗都继承自动物类,我们理应能够这样做:

#include <array>

#include <iostream>

// Cat and Dog from the example above

int main()

{

const Cat fred{ "Fred" };

const Cat misty{ "Misty" };

const Cat zeke{ "Zeke" };

const Dog garbo{ "Garbo" };

const Dog pooky{ "Pooky" };

const Dog truffle{ "Truffle" };

// Set up an array of pointers to animals, and set those pointers to our Cat and Dog objects

const auto animals{ std::to_array<const Animal*>({&fred, &garbo, &misty, &pooky, &truffle, &zeke }) };

// Before C++20, with the array size being explicitly specified

// const std::array<const Animal*, 6> animals{ &fred, &garbo, &misty, &pooky, &truffle, &zeke };

for (const auto animal : animals)

{

std::cout << animal->getName() << " says " << animal->speak() << '\n';

}

return 0;

}

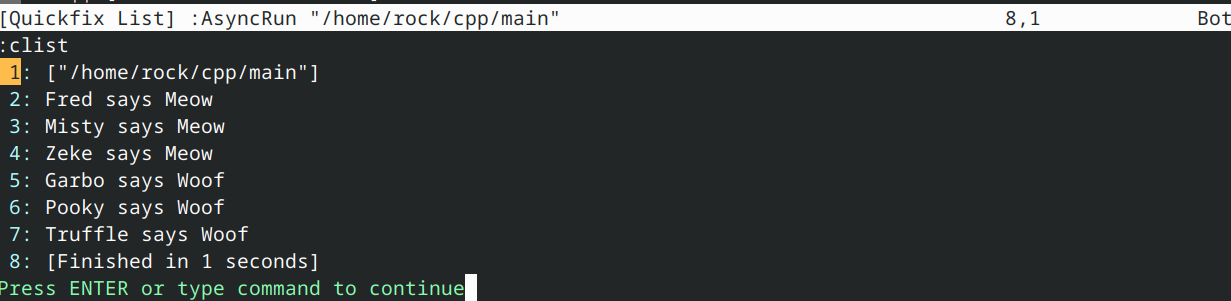

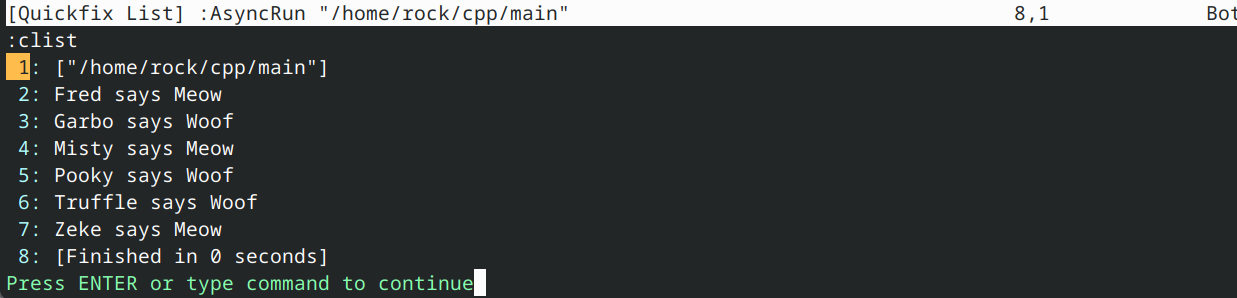

虽然这段代码能编译并执行,但遗憾的是,由于数组“animals”的每个元素都是指向Animal类的指针,导致animal->speak()会调用Animal::speak(),而非我们期望的派生类版本的speak()。输出结果为:

尽管这两种技术都能为我们节省大量时间和精力,但它们存在相同的问题:指向基类的指针或引用会调用基类的函数版本,而非派生类的版本。要是能让这些基类指针调用派生类的函数版本而非基类版本就好了……

猜猜虚拟函数是用来做什么的? 😃

测验时间

- 我们上面的动物/猫/狗示例无法按预期工作,因为指向动物的引用或指针无法访问派生版本的speak()函数——该函数本应为猫或狗返回正确值。解决此问题的方案之一是将speak()函数返回的数据作为动物基类的一部分提供访问(类似于通过成员m_name访问动物名称的方式)。

请在上述课程中更新Animal、Cat和Dog类,为Animal新增名为m_speak的成员变量并进行适当初始化。修改后的程序应能正常运行:

#include <array>

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

const Cat fred{ "Fred" };

const Cat misty{ "Misty" };

const Cat zeke{ "Zeke" };

const Dog garbo{ "Garbo" };

const Dog pooky{ "Pooky" };

const Dog truffle{ "Truffle" };

// Set up an array of pointers to animals, and set those pointers to our Cat and Dog objects

const auto animals{ std::to_array<const Animal*>({ &fred, &garbo, &misty, &pooky, &truffle, &zeke }) };

// Before C++20, with the array size being explicitly specified

// const std::array<const Animal*, 6> animals{ &fred, &garbo, &misty, &pooky, &truffle, &zeke };

for (const auto animal : animals)

{

std::cout << animal->getName() << " says " << animal->speak() << '\n';

}

return 0;

}

显示方案

#include <array>

#include <string>

#include <string_view>

#include <iostream>

class Animal

{

protected:

std::string m_name;

std::string m_speak;

// We're making this constructor protected because

// we don't want people creating Animal objects directly,

// but we still want derived classes to be able to use it.

Animal(std::string_view name, std::string_view speak)

: m_name{ name }, m_speak{ speak }

{

}

// To prevent slicing (covered later)

Animal(const Animal&) = delete;

Animal& operator=(const Animal&) = delete;

public:

std::string_view getName() const { return m_name; }

std::string_view speak() const { return m_speak; }

};

class Cat: public Animal

{

public:

Cat(std::string_view name)

: Animal{ name, "Meow" }

{

}

};

class Dog: public Animal

{

public:

Dog(std::string_view name)

: Animal{ name, "Woof" }

{

}

};

int main()

{

const Cat fred{ "Fred" };

const Cat misty{ "Misty" };

const Cat zeke{ "Zeke" };

const Dog garbo{ "Garbo" };

const Dog pooky{ "Pooky" };

const Dog truffle{ "Truffle" };

// Set up an array of pointers to animals, and set those pointers to our Cat and Dog objects

const auto animals{ std::to_array<const Animal*>({ &fred, &garbo, &misty, &pooky, &truffle, &zeke }) };

// Before C++20, with the array size being explicitly specified

// const std::array<const Animal*, 6> animals{ &fred, &garbo, &misty, &pooky, &truffle, &zeke };

// animal is not a reference, because we're looping over pointers

for (const auto animal : animals)

{

std::cout << animal->getName() << " says " << animal->speak() << '\n';

}

return 0;

}

- 为什么上述解决方案并非最优?

提示:请考虑猫和狗在未来状态中,我们需要通过更多方式区分它们的情况。

提示:请思考在初始化时需要设置成员变量会如何限制你的实现。

显示方案

当前方案存在诸多不足之处。

首先,每当需要区分猫和狗时,我们都必须在Animal类中新增一个成员变量。随着时间推移,Animal类的内存占用可能变得相当庞大,且结构日益复杂!

其次,该方案仅在基类成员能在初始化时确定时有效。例如若speak()函数对每种动物返回随机结果(如调用Dog::speak()可能返回“汪”、“呜呜”或“嗷嗷”),此类方案便会变得笨拙且失效。

第三,由于 speak() 是 Animal 的成员函数,猫狗的 speak() 行为将完全一致(即始终返回 m_speak)。若需实现猫狗差异化行为(例如让狗返回随机叫声),则必须在 Animal 中添加额外逻辑,这将使 Animal 变得更加复杂。

浙公网安备 33010602011771号

浙公网安备 33010602011771号