Tail call optimization

Tail call is any function that is in tail position, the final action to be peformed before a function returns.

Tail call optimization (TCO) is a technique used by programming languages to optimize recursive funtion calls. In simple terms, TCO allows a function to call itself without adding a new stack frame to the call stack. Instead, it reuses the existing stack frame and updates the parameters and the program counter.

TCO in Detail

In programming languages, a function creates a new stack frame that contains the function's arguments, local variables, and the return address.

When a function calls itself recursively, a new stack frame is added to the call stack for each call. This creates a chain of stack frames that can grow very large for large inputs, resulting in a stack overflow error.

Tail call optimization allows a function to reuse the existing stack frame for a recursive call, eliminating the need for a new stack frame.

This optimization is only possible if the recursive call is the last operation in the function, hence the name “tail call.” If there is any code that executes after the recursive call, TCO cannot be applied.

Case1

A function that calculates the factorial of a number using recursion:

function factorial(n) {

if (n === 0) {

return 1;

} else {

return n * factorial(n — 1);

}

}

the call stack looks like this when we call factorial(5).

Each call to factorial() adds a new frame to the call stack, this can cause a stack overflow error if the input is too large.

factorial(5)

factorial(4)

factorial(3)

factorial(2)

factorial(1)

factorial(0)

Case2

Rewrite the function to use TCO:

function factorial(n, acc = 1) {

if (n === 0) {

return acc;

} else {

return factorial(n - 1, acc * n);

}

}

acc is an accumulator variable that keeps track of the result of each multiplication. Instead of returning n*factorial(n-1), pass the result of acc*n as the second argument to the next recursive call.

This allows us to eliminate the need for a new stack frame for each recursive call.

the call stack looks like this when call factorial(5)

factorial(5, 1)

factorial(4, 5)

factorial(3, 20)

factorial(2, 60)

factorial(1, 120)

factorial(0, 120)

Then the compiler has the option to optimize this code and not create any new stack frame for the respective calls.

Instead use the current one and update the parameters and program counter.

Computationally, this code becomes equivalent to a solution using loops.

TCO is not always easy to implement especially in languages that do not support it natively. In some cases, you may need to rewrite your code to use TCO or use a library or tool that provides TCO support. However, the benefits of TCO are significant, especially for performance-critical code.

Benefits of TCO

There are several benefits of using TCO in your code:

- It improves the performance of recursive functions by reducing the number of stack frames created, which can reduce the risk of stack overflow errors and improve the speed of your code.

- It allows you to write more concise and readable code by avoiding the need for loops or iteration in some cases.

Brawbacks of TCO

While TCO has many benefits, it also has some drawbacks:

- TCO is not supported by all programming languages, which can limit its use in some cases.

- TCO can make debugging more difficult because the call stack may not reflect the actual call order of the functions.

- TCO can be challenging to implement in some cases, especially if the function has side effects or relies on external state.

In conclusion, TCO is a powerful optimization technique that can improve the performance and reliability of your code. While it may require some extra effort to implement in some cases, the benefits are well worth it, especially for performance-critical code. Hopefully, this article has given you a better understanding of TCO and how it can be used to optimize your recursive functions.

Tail call in Assembly

When tail call optimization occurs, the compiler emits a jmp instruction for the tail call instead of call. This skips over the bookkeeping that would normally allow the callee g() to return back to the caller f(), like creating a new stack frame or pushing the return address.

Instead f() jumps directly to g() as if it were part of the same function, and g() returns directly to whatever function called f().

This optimization is safe because f()'s stack frame is no longer needed once the tail call has begun, since it is no longer possible to access any of f()'s local variables.

It has two very important properties unlock new possibilities in the kinds of algorithms we can write.

- First, it reduces the stack memory from from

O(n)toO(1)when makingnconsecutive tail calls, which is important because stack memory is limited and stack overflow will crash your program. This means that certain algorithms are not actually safe to write unless this optimization is performed. - Secondly,

jmpeliminates the performance overhead ofcall, such that a function call can be just as efficient as any other branch. These two properties enable us to use tail calls as an efficient alternative to normal iterative control structures likefororwhile

The trouble with Interpreter Loops

Why C compilers struggle with Interpreter main loops?

- The larger a function is, and the more complex and connected its control flow, the harder it is for the compiler’s register allocator to keep the most important data in registers.

- When fast paths and slow paths are intermixed in the same function, the presence of the slow paths compromises the code quality of the fast paths.

Specify the problem in Interpreter

Interpreter loops and protobuf parsers

the nature of the protobuf wire format makes them more similar to each other.

The protobuf wire format is a series of tag/value pairs, where the tag contains a field number and wire type.

This tag acts similarly to an interpreter opcode:

- it tells us what operation we need to perform to parse this field’s data.

- Like interpreter opcodes, protobuf field numbers can come in any order, so we have to be prepared to dispatch to any part of the code at any time.

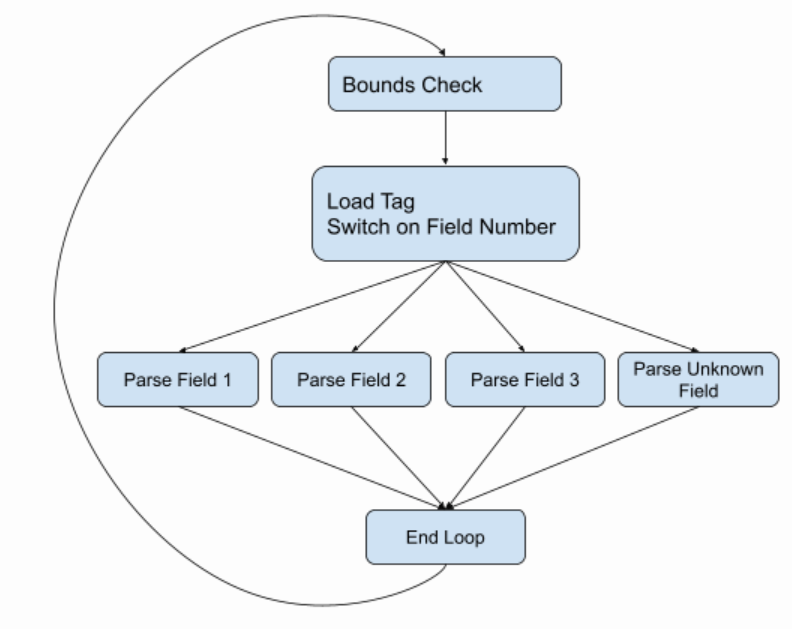

The natural way to write such a parser is to have a while loop surrounding a switch statement, and indeed this has been the state of the art in probobuf parsing for basically as long as protobufs have existed. And the control flow is represented like this:

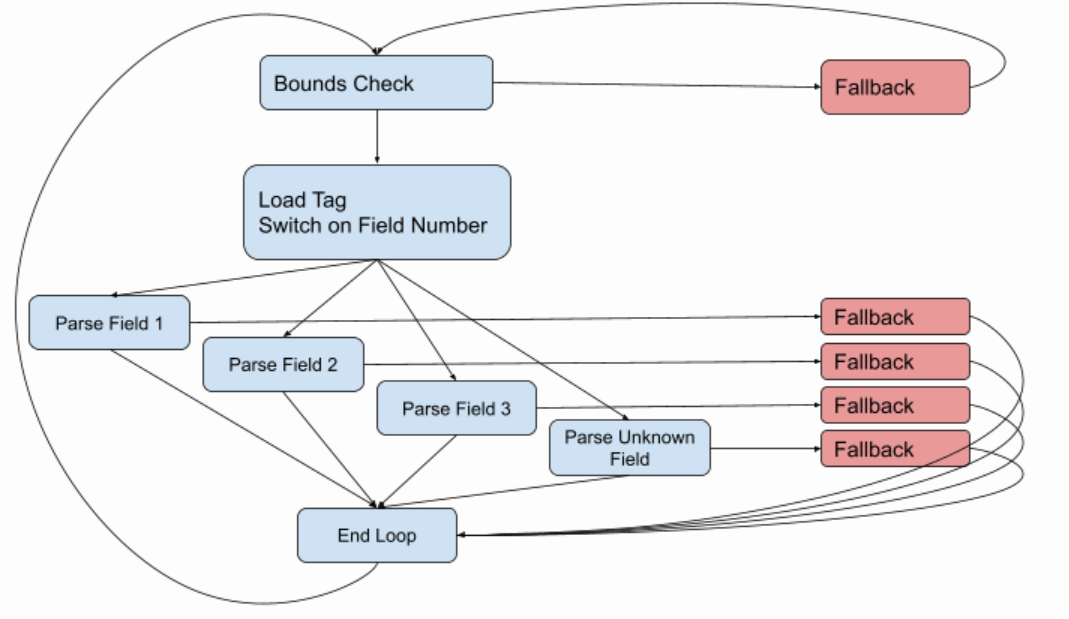

But this is incomplete, because almost at every stage there are things that can go wrong. The wire type could be wrong, or we could corrupt data, or we just hit the current buffer. So the full control flow graph looks more like:

When we hit a hard case we have to execute some fallback code to handle it. These fallback paths are usually bigger and more complicated than the fast paths, touch more data, and often even make out-of-line calls to other functions to handle the more complex cases.

The control flow graph paired with a profile should give the compiler all of the information if needs to generate the most optimal code.

When facing a big and connected function, compiler spills an important variable when operator want it to keep it in a register. It hoists stack frame manipulation that we want to shrink wrap around a fallback function invocation. It merges identical code paths that we wanted to keep separate for branch prediction reasons.

How tail calls can help solve both of these problems

In the design of upb, there is no single big parse function and instead of giving each opeartion its own small function, Each function tail calls the next operation in sequence.

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stddef.h>

#include <string.h>

typedef void *upb_msg;

struct upb_decstate;

typedef struct upb_decstate upb_decstate;

// The standard set of arguments passed to each parsing function.

// Thanks to x86-64 calling conventions, these will be passed in registers.

#define UPB_PARSE_PARAMS \

upb_decstate *d, const char *ptr, upb_msg *msg, intptr_t table, \

uint64_t hasbits, uint64_t data

#define UPB_PARSE_ARGS d, ptr, msg, table, hasbits, data

#define UNLIKELY(x) __builtin_expect(x, 0)

#define MUSTTAIL __attribute__((musttail))

const char *fallback(UPB_PARSE_PARAMS);

const char *dispatch(UPB_PARSE_PARAMS);

// Code to parse a 4-byte fixed field that uses a 1-byte tag (field 1-15).

const char *upb_pf32_1bt(UPB_PARSE_PARAMS) {

// Decode "data", which contains information about this field.

uint8_t hasbit_index = data >> 24;

size_t ofs = data >> 48;

if (UNLIKELY(data & 0xff)) {

// Wire type mismatch (the dispatch function xor's the expected wire type

// with the actual wire type, so data & 0xff == 0 indicates a match).

MUSTTAIL return fallback(UPB_PARSE_ARGS);

}

ptr += 1; // Advance past tag.

// Store data to message.

hasbits |= 1ull << hasbit_index;

memcpy((char*)msg + ofs, ptr, 4);

ptr += 4; // Advance past data.

// Call dispatch function, which will read the next tag and branch to the

// correct field parser function.

MUSTTAIL return dispatch(UPB_PARSE_ARGS);

}

And the assembly code generated by Clang is like:

upb_pf32_1bt: # @upb_pf32_1bt

mov rax, r9

shr rax, 24

bts r8, rax

test r9b, r9b

jne .LBB0_1

mov r10, r9

shr r10, 48

mov eax, dword ptr [rsi + 1]

mov dword ptr [rdx + r10], eax

add rsi, 5

jmp dispatch # TAILCALL

.LBB0_1:

jmp fallback # TAILCALL

There is no prologue or epilogue, no register spills, indeed there is no usage of the stack whatsoever. The only exits are jmps from the two tail calls, but no code is required to forward the parameters, because the arguments are already sitting in the correct registers. The only improvement is to get a conditional jump for the tail call, jne fallback, instead of jne followed by jmp.

In the implementation of upb they take an interpreter loop that is conceptually a big complicated function and programming it block by block, transferring control flow from one to the next via tail calls.

They have full control of the register allocation at every block boundary(at least 6 registers), and as long as the function is simple enough to not spill those six registers. Most iimportant state are keeped in registers throughout all of the fast paths.

Every instruction sequence independently can be optimized, and the compiler will treat each sequence as independent too because they are in separate functions (with option noinline can prevent inling if necessary). This solves the problem that described as slowest path with fallback, fast paths will not be suffered will be gurarnteed. The nice assembly sequence above is effectively frozen, unaffected by any changes by any other changes.

References

[1] Parsing Protobuf at 2+GB/s: How I Learned To Love Tail Calls in C

[2] Tail Call Optimization: What it is? and Why it Matters?

浙公网安备 33010602011771号

浙公网安备 33010602011771号