File system

8 File system

xv6构建的文件系统十分小巧并且功能齐全,虽然与现在的主流文件系统(FAT32、EXT4…)仍有差距,但文件系统实现的思想都大同小异,所以xv6的文件系统值得我们学习。

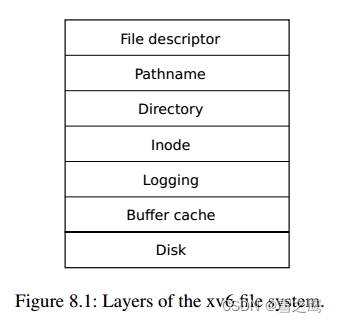

文件系统使用分层的思想:每一层分别实现某一单一功能;下一层为上一层提供接口。

各层实现功能:

- File descriptor:抽象了管道、设备、文件等资源, 即一切皆文件

- Pathname:提供了/usr/xxx这样的分层路径名,可以通过递归来解析

- Directory:将每个目录实现为一种特殊的Inode,把文件命名和Inode绑定

- Inode:将数据块Block和唯一的Inode号绑定

- Logging:实现崩溃恢复,即所有块都更新或不更新

- Buffer cache:磁盘在内存的缓冲区,实现磁盘访问的缓存和同步(缓冲区一次只有一个进程可以访问)

- Disk:读写磁盘上的块

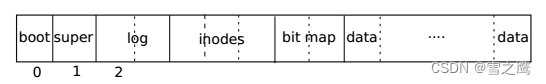

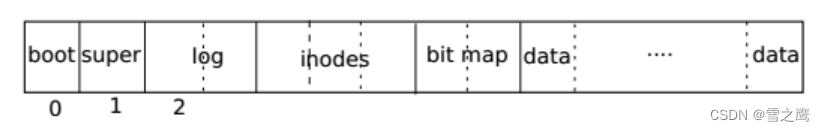

文件系统在磁盘的组织形式也很简单。文件系统按照下图将各部分写入磁盘后,之后的读写都要按照下图的格式来进行

Buffer cache

Buffer cache层(bio.c)主要有两个作用:

- 缓存磁盘块:将磁盘上的block在内存中形成对应的副本cache,之后的操作都是在cache中进行。(磁盘的最小读写单位为扇区sector,xv6中

1 buffer = 1 block = 2 sectors,每次改变几个字节就读写磁盘的代价太大,所以引入了缓冲区)- 同步访问磁盘块:即一次只能有一个进程访问cache。(防止并发问题)

Buffer cache层的功能主要由bread()和bwrite()实现。

// Return a locked buf with the contents of the indicated block.

// buf缓冲区没有才从磁盘读(read:disk->buf)

struct buf *

bread(uint dev, uint blockno)

{

struct buf *b;

b = bget(dev, blockno);

if (!b->valid)

{

virtio_disk_rw(b->dev, b, 0);

b->valid = 1;

}

return b;

}

// Write b's contents to disk. Must be locked.

// 直接buf写数据到磁盘(write:buf->disk,注:这里没有进行延迟写入的操作)

void bwrite(struct buf *b)

{

if (!holdingsleep(&b->lock))

panic("bwrite");

virtio_disk_rw(b->dev, b, 1);

}

// Release a locked buffer.

// Move to the head of the MRU list.

void brelse(struct buf *b)

{

if (!holdingsleep(&b->lock))

panic("brelse");

releasesleep(&b->lock);

acquire(&bcache.lock);

b->refcnt--;

if (b->refcnt == 0) // 会将此block插入到链表头,作为MRU

{

// no one is waiting for it.

b->next->prev = b->prev;

b->prev->next = b->next;

b->next = bcache.head.next;

b->prev = &bcache.head;

bcache.head.next->prev = b;

bcache.head.next = b;

}

release(&bcache.lock);

}

对于同步的实现,很容易想到是利用锁完成的。bwrite()的实现也很简单,直接写入磁盘对应的block即可;而bread()需要调用bget(),并且每次bread()之后都需要调用brelse()。

bget():

struct

{

struct spinlock lock;

struct buf buf[NBUF];

// Linked list of all buffers, through prev/next.

// head.next is most recently used.

struct buf head;

} bcache;

// Look through buffer cache for block on device dev.

// If not found, allocate a buffer.

// In either case, return locked buffer.

static struct buf *

bget(uint dev, uint blockno)

{

struct buf *b;

acquire(&bcache.lock);

// 如果对应block在buffer cache中

for (b = bcache.head.next; b != &bcache.head; b = b->next)

{

if (b->dev == dev && b->blockno == blockno)

{

b->refcnt++; // 文件引用+1

release(&bcache.lock);

acquiresleep(&b->lock);

return b;

}

}

// 不在则返回一个空闲Block

for (b = bcache.head.prev; b != &bcache.head; b = b->prev) // 去链表尾找LRU的block

{

if (b->refcnt == 0)

{

b->dev = dev;

b->blockno = blockno;

b->valid = 0;

b->refcnt = 1;

release(&bcache.lock);

acquiresleep(&b->lock);

return b;

}

}

panic("bget: no buffers");

}

bget()的作用是获得buffer cache中buffer,它的原理也很简单:如果索取的block号在cache中,refcnt+1并返回对应buffer,不在则取出一个refcnt=0的buffer返回。

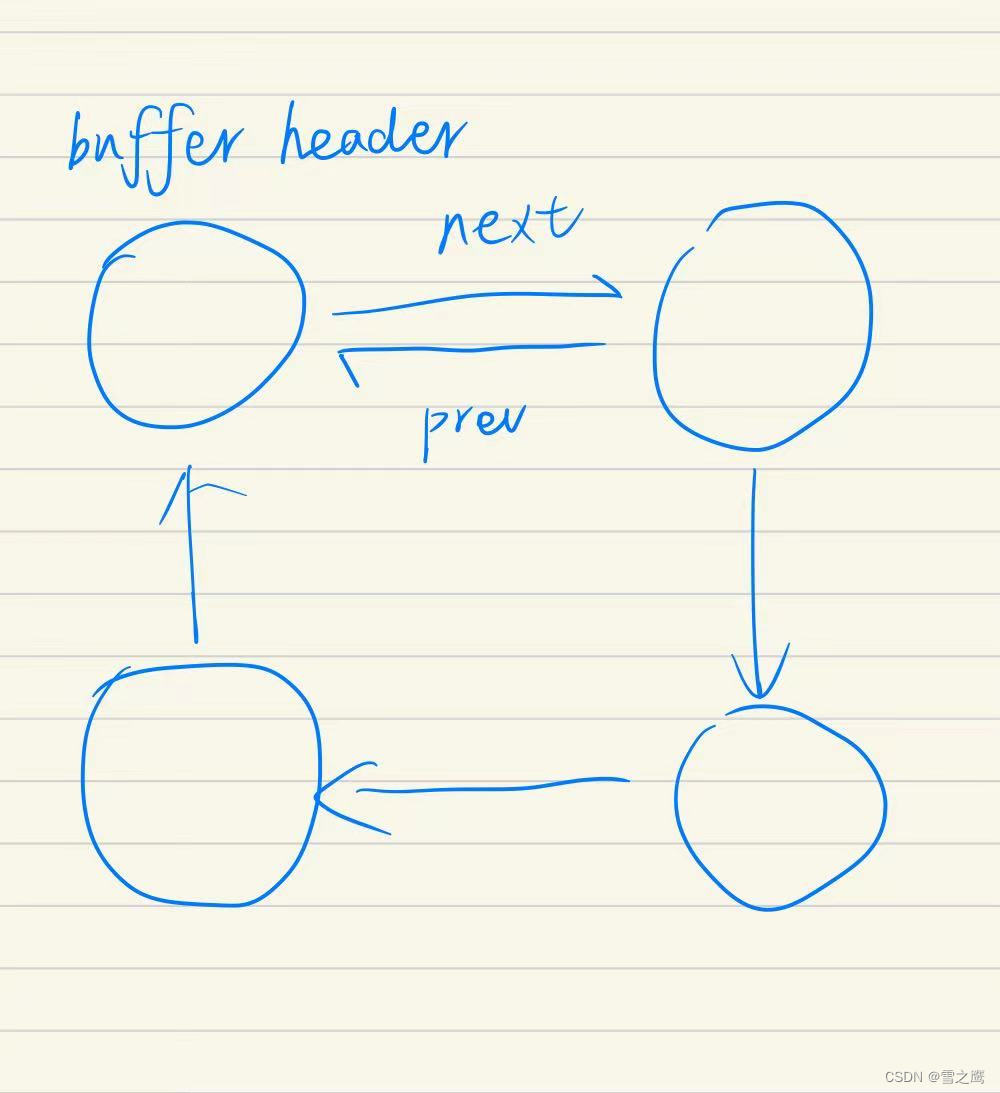

需要注意这里使用的置换算法LRU(Least Recently Used)。这里使用链表实现,最少使用的buffer会被挤到环形链表的尾巴上(header->prev),而最常使用的则在链表的头部之后(header->next)。在代码里,bget()如果找不到cache对应的block,就会去链表尾找block替换,因为这里是Least Recently Used;而brelse()会将刚读完释放的block插入到链表头,作为MRU(Most Recently Used)。

Logging

Logging层(log.c)的主要作用:

- 实现文件系统的崩溃恢复机制

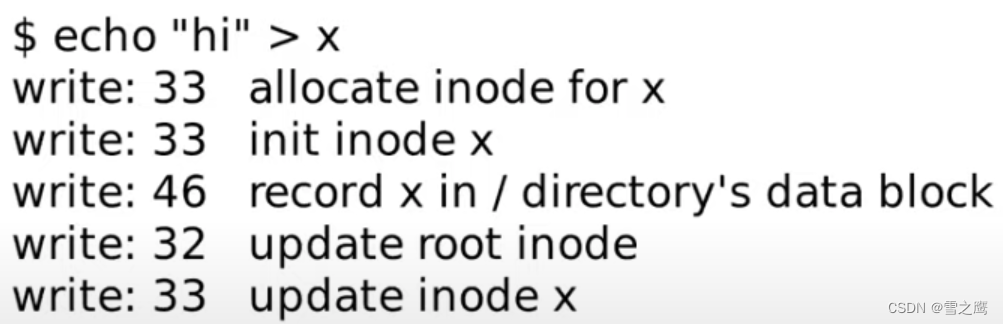

举个例子,假如没有logging层,我们进行echo操作:

- 首先是分配inode,因为首先写的是block 33

- 之后inode被初始化,然后又写了一次block 33

- 之后是写block 46,是将文件x的inode编号写入到x所在目录的inode的data block中

- 之后是更新root inode,因为文件x创建在根目录,所以需要更新根目录的inode的size字段,以包含这里新创建的文件x

- 最后再次更新文件x的inode

如果我们在33和46这两步之间发生崩溃,整个系统关机,再重启时系统崩溃前的操作已经完成,崩溃后的操作还没有完成,然而系统会默认它已经完成。造成的问题就是这个Inode没有出现在任何目录中,我们无法删除它,所以就需要一种崩溃恢复的机制来解决这种问题。

分析上面的现象,会发现它们都是出现在写入时出现的BUG。既然多个写磁盘的操作分开就会出现问题,我们的解决办法就是让它变成一个原子操作:要么一次完成全部写入,要么什么都不写入。这也是Logging层实现的目的。

Logging的原理

Logging的基本思想还是很简单的:它将磁盘又多分割了一个Log分区,当我们要对磁盘进行写入时,我们不会直接写到磁盘的data部分,而是先写到log中。在之后的某一时间,我们会commit文件系统的操作,这时log中所有的内容才会被写入到data里,并且log清除,总共分4步:

- log writes:在log header中记录需要更新的log

- commint op:将log header中的记录写入到disk中

- install:将log中的block写入到disk

- clean log:清除log中的所有内容

为什么使用Log就可以实现崩溃恢复呢?

- 崩溃发生在1和2之间:我们只是在内存中的log header中做了记录,并未落盘(写入disk里)。在重启时只需检查disk中的log header有无记录,由于内存中的log header丢失了,所以我们什么都不需要做,系统会当作无事发生。

- 崩溃发生在2和3之间:log header中的记录已经落盘。重启后看到log header中有记录,这时就需要把disk中log的内容写入到disk对应的data区域,并且写完后log header清零。

- 崩溃发生在3和4之间:此时已有log写入到disk中。重启后做的工作和第2步一样,因为重复写入相同位置是没有问题的。

总之,加入了Log后,我们可以做到某个事件的全写入或者全不写入,实现了原子性。在commit前的操作视为全不写入,在commit后的操作视为全写入。

Logging的实现

了解了Logging的原理后,我们来看看它的实现细节。

log_wirte():

// Caller has modified b->data and is done with the buffer.

// Record the block number and pin in the cache by increasing refcnt.

// commit()/write_log() will do the disk write.

//

// log_write() replaces bwrite(); a typical use is:

// bp = bread(...)

// modify bp->data[]

// log_write(bp)

// brelse(bp)

// 将更新块记录领导log head中

// 注意区分write_log

void log_write(struct buf *b)

{

int i;

int dev = b->dev;

if (log[dev].lh.n >= LOGSIZE || log[dev].lh.n >= log[dev].size - 1)

panic("too big a transaction");

if (log[dev].outstanding < 1)

panic("log_write outside of trans");

acquire(&log[dev].lock);

for (i = 0; i < log[dev].lh.n; i++)

{

if (log[dev].lh.block[i] == b->blockno) // log absorbtion

break;

}

log[dev].lh.block[i] = b->blockno;

if (i == log[dev].lh.n)

{ // Add new block to log?

bpin(b); // 引用计数+1(假设)

log[dev].lh.n++;

}

release(&log[dev].lock);

}

注释写明用log_wirte()代替了bwrite(),之后的写磁盘操作都调用log_wirte(),所以bwrite()的实现才会那么简单。

log_wirte()对应原理的第一步。作用就是记录更新块,即要写入log中的块,只需改变log header。每当有写入操作的系统调用发生时,都会调用log_wirte()来记录。

commit():

static void

commit(int dev)

{

if (log[dev].lh.n > 0)

{

write_log(dev); // Write modified blocks from cache to log

write_head(dev); // Write header to disk -- the real commit

install_trans(dev); // Now install writes to home locations

log[dev].lh.n = 0;

write_head(dev); // Erase the transaction from the log

}

}

之后的三步封装在了commit()函数中,因为它们基本都是连在一起调用的,而非log_write()与写操作一起调用。

write_log():

// Copy modified blocks from cache to log.

// cache block->log block

// log[dev].lh.block[tail]由log_write更新

static void

write_log(int dev)

{

int tail;

for (tail = 0; tail < log[dev].lh.n; tail++)

{

struct buf *to = bread(dev, log[dev].start + tail + 1); // log block

struct buf *from = bread(dev, log[dev].lh.block[tail]); // cache block

memmove(to->data, from->data, BSIZE);

bwrite(to); // write the log

brelse(from);

brelse(to);

}

}

write_log()实现cache block->log block(both memory and disk),将前面log header记录的block写入log中,log部分(除了log header)落盘。

write_head():

// Write in-memory log header to disk.

// This is the true point at which the

// current transaction commits.

static void

write_head(int dev)

{

struct buf *buf = bread(dev, log[dev].start);

struct logheader *hb = (struct logheader *)(buf->data);

int i;

hb->n = log[dev].lh.n;

for (i = 0; i < log[dev].lh.n; i++)

{

hb->block[i] = log[dev].lh.block[i];

}

bwrite(buf);

brelse(buf);

}

在这一步我们才将log header部分落盘,它是真正意义上的commit。因为我们的崩溃恢复就是靠因为log header的不同才有不同的处理流程。在这之前的崩溃我们可以不关心,在这之后我们就需要依靠log header来恢复数据了。

install_trans():

// Copy committed blocks from log to their home location

static void

install_trans(int dev)

{

int tail;

for (tail = 0; tail < log[dev].lh.n; tail++)

{

struct buf *lbuf = bread(dev, log[dev].start + tail + 1); // read log block

struct buf *dbuf = bread(dev, log[dev].lh.block[tail]); // read dst

memmove(dbuf->data, lbuf->data, BSIZE); // copy block to dst

bwrite(dbuf); // write dst to disk

bunpin(dbuf);

brelse(lbuf);

brelse(dbuf);

}

}

install_trans()实现log block->data block(both memory and disk),我们的数据经过log之后终于来到了属于它的block。

在清除了log header之后,一个logging的流程结束。我们再来看看重启是会发生什么。

static void

recover_from_log(int dev)

{

read_head(dev);

install_trans(dev); // if committed, copy from log to disk

log[dev].lh.n = 0;

write_head(dev); // clear the log

}

有了前面的Logging,重启的操作就很简单。我们只需要知道log header有没有东西,之后就能恢复了。

Challenges

write ahead rule

write ahead rule:预写规则,所有的写入都需要先经过Log才能落盘。

假设进程P已经对block44进行了写入,然而再写入别的block时buffer满了,根据置换算法需要置换出block44。这样是不行的,block44虽然已经写入了log header,但是并没有写入log data中,这样做的后果就是把block44撤回了,原本该写入block的数据没了,肯定是不行的。

置换发生在bget()中,我们发现bget()是通过判断refcnt来决定是否置换的。所以解决办法是在调用log_write()时就让refcnt++,相当于只要是写操作就占有一个refcnt,保证该block不会被置换掉。

log大小

文件系统操作必须适配log的大小,只有这样才能遵循write ahead rule。

xv6中log的大小为30,是因为30比任何一个xv6的文件系统操作都大。然而当我们要强行写一个大文件时,写入的block数就不可避免地大于30了,可以看到filewrite对大文件处理:

filewrite():

// Write to file f.

// addr is a user virtual address.

int filewrite(struct file *f, uint64 addr, int n)

{

···

else if (f->type == FD_INODE)

{ // 文件

// write a few blocks at a time to avoid exceeding

// the maximum log transaction size, including

// i-node, indirect block, allocation blocks,

// and 2 blocks of slop for non-aligned writes.

// this really belongs lower down, since writei()

// might be writing a device like the console.

int max = ((MAXOPBLOCKS - 1 - 1 - 2) / 2) * BSIZE;

int i = 0;

while (i < n)

{

int n1 = n - i;

if (n1 > max)

n1 = max;

begin_op(f->ip->dev);

ilock(f->ip);

if ((r = writei(f->ip, 1, addr + i, f->off, n1)) > 0)

f->off += r;

iunlock(f->ip);

end_op(f->ip->dev);

if (r < 0)

break;

if (r != n1)

panic("short filewrite");

i += r;

}

ret = (i == n ? n : -1);

}

else

{

panic("filewrite");

}

return ret;

}

filewrite()将大文件分成了多次写block操作。这确实破坏了我们一直强调的原子性,但这里的妥协是不对文件系统造成损坏,不让文件系统处于不正确的状态中。

并发问题

文件系统的并发问题不仅存在与block的同步上,还有日志的问题。

假设现在有两个并发执行的write_log(),t0写了14log block还没写完,t1写了之后的16个block,此时commit的话就违背了write ahead rule。所以我们需要在每次写入log之前就进行检查,如果写入的长度超了就只有下次再写入了,这里就要提到包裹住文件系统调用(FS syscall)的两个函数:begin_op()和end_op()。

begin_op():

// called at the start of each FS system call.

void begin_op(int dev)

{

acquire(&log[dev].lock);

while (1)

{

if (log[dev].committing)

{

sleep(&log, &log[dev].lock);

}

else if (log[dev].lh.n + (log[dev].outstanding + 1) * MAXOPBLOCKS > LOGSIZE) // log[dev].outstanding + 1:当前存在别的进程在进行FS systemcall,不知道其写入log的大小,所以假定最大(MAXOPBLOCKS)

{

// this op might exhaust log space; wait for commit.

// 为了避免并发问题,我们必须限制一次写入log的block大小

sleep(&log, &log[dev].lock);

}

else

{

log[dev].outstanding += 1;

release(&log[dev].lock);

break;

}

}

}

如果这次写入的blocks数超过了LOGSIZE,begin_op()会将此进程睡眠,反之则将outstanding+1并继续。

这里涉及到MAXOPBLOCKS和outstanding两个量。MAXOPBLOCKS将一次写入的最大block数定义为10,也就是说我们是拿此次写入最大blocks的情况来判断的;outstanding用来记录并发进行的FS syscall的个数。

end_op():

// called at the end of each FS system call.

// commits if this was the last outstanding operation.

void end_op(int dev)

{

int do_commit = 0;

acquire(&log[dev].lock);

log[dev].outstanding -= 1;

if (log[dev].committing)

panic("log[dev].committing");

if (log[dev].outstanding == 0) // 只用FS syscall都结束了才能commit

{

do_commit = 1;

log[dev].committing = 1;

}

else

{

// begin_op() may be waiting for log space,

// and decrementing log[dev].outstanding has decreased

// the amount of reserved space.

wakeup(&log); //唤醒begin_op()中因为LOGSIZE睡眠的进程

}

release(&log[dev].lock);

if (do_commit)

{

// call commit w/o holding locks, since not allowed

// to sleep with locks.

commit(dev);

acquire(&log[dev].lock);

log[dev].committing = 0;

wakeup(&log);

release(&log[dev].lock);

}

}

commit操作是在end_op()函数中才会调用,只有在FS syscall都结束了才能commit。就这样,我们通过在FS syscall前后填加begin_op()和end_op()保证了文件系统的并发性。

Inode

我们现在已经实现的Buffer cache层和Logging层,如果忽略用于崩溃恢复的Logging层,我们只能block进行读写,而要实现文件的操作是不够的,所以Inode层就是来做这件事。

Inode层(fs.c)的主要作用:

- 将数据块Block和唯一的Inode号绑定,实现“Inode”版的文件

dinode和inode

我们先来看看Inode里面存的是什么?首先是磁盘中的Inode:

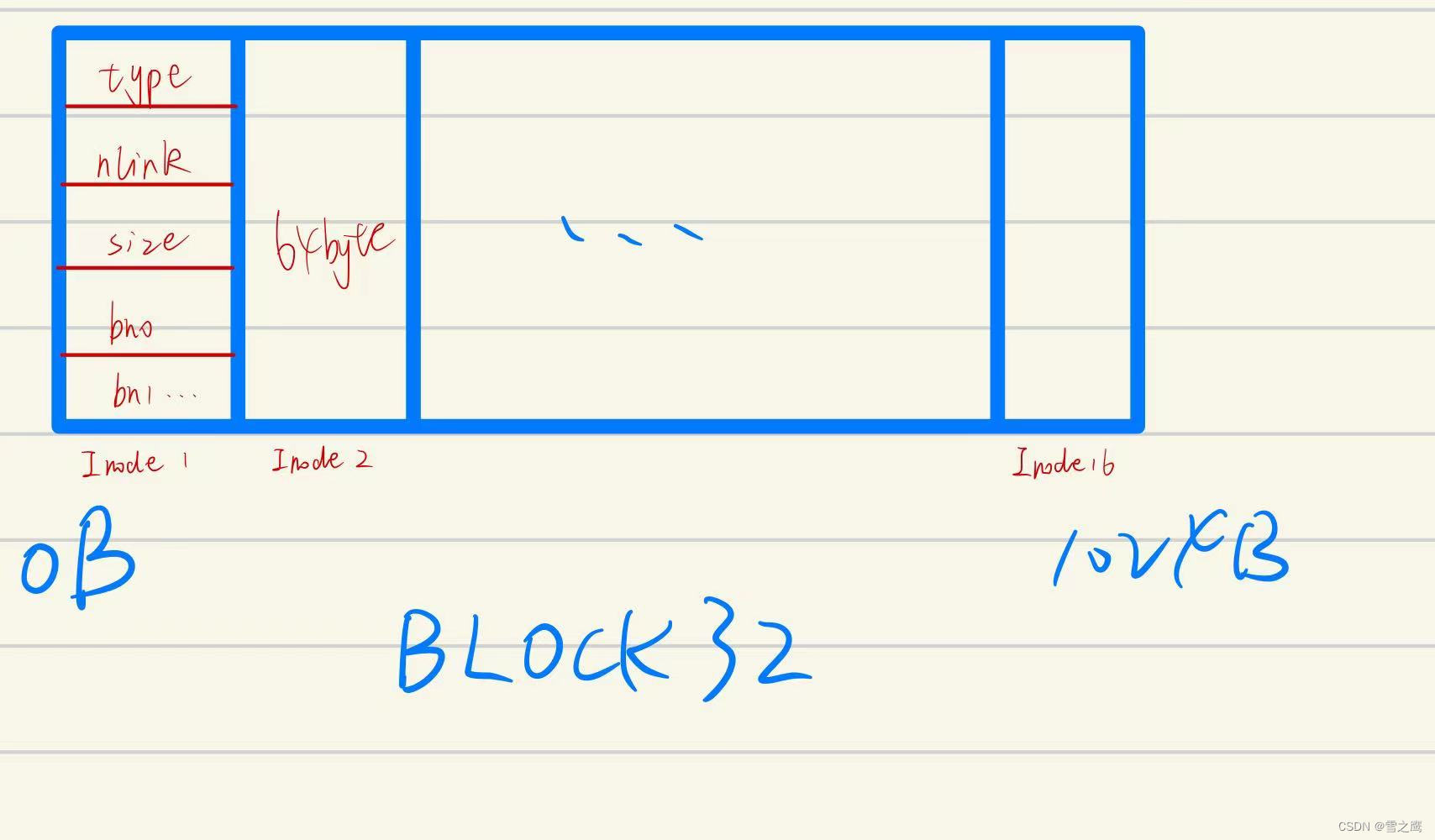

磁盘中每个Inode占64Byte,在Block32里总共有16个Inode。磁盘中Inode里的内容我们可以通过dinode这个结构体解析,它代表磁盘中Inode在内存中的映射。换句话说,我们从磁盘写入和读出的数据格式都是dinode。

dinode将disk里的信息原封不动地呈现,而要进行一些其他操作,仅靠dinode结构体里的变量是不够的,所以我们之后会将dinode(on-disk)转换成inode(in-memory)形式。

// On-disk inode structure

// 用于将磁盘中读取的buf->data数据强转为Inode形式

struct dinode

{

short type; // File type

short major; // Major device number (T_DEVICE only)

short minor; // Minor device number (T_DEVICE only)

short nlink; // Number of links to inode in file system

uint size; // Size of file (bytes)

uint addrs[NDIRECT + 2]; // Data block addresses

};

// in-memory copy of an inode

struct inode

{

uint dev; // Device number

uint inum; // Inode number

int ref; // Reference count

struct sleeplock lock; // protects everything below here

int valid; // inode has been read from disk?

short type; // copy of disk inode

short major;

short minor;

short nlink;

uint size;

uint addrs[NDIRECT + 2];

};

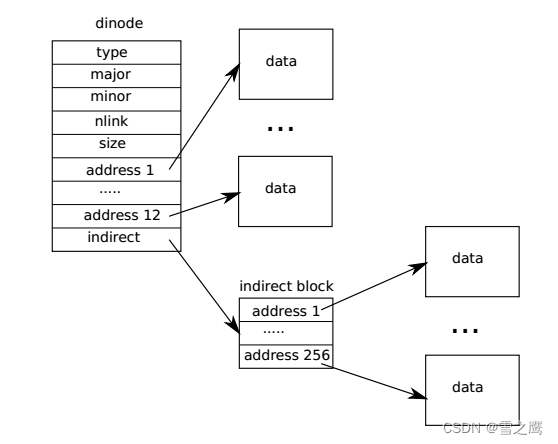

Inode的作用是将blocks组织起来构成文件,在dinode和inode结构体里面是用addrs来记录。其中addr1-addr12为直接索引,它们存储的就是对应的block号;而addr13是间接索引,相当于它指向的block是一个目录,里面存放的也是索引号。所以,一个Inode(文件)最大拥有12+256=268个block。(本章对应的Lab就是要求使用二级索引来增加Inode的block数)

这里还要着重说一下inode中的ref和nlink:

- ref:与进程相关,比如进程打开文件,对应的inode->ref++

- nlink:与目录相关,比如目录中包含了某文件,对应的inode->nlink++

所以我们看到inode比dinode多的一些变量不是随便加的。正是因为ref记录着进程打开文件的次数,nlink记录目录包含文件的次数,我们才选择了这样的设计。

ialloc():

// Allocate an inode on device dev.

// Mark it as allocated by giving it type type.

// Returns an unlocked but allocated and referenced inode.

struct inode *

ialloc(uint dev, short type)

{

int inum;

struct buf *bp;

struct dinode *dip;

for (inum = 1; inum < sb.ninodes; inum++)

{

bp = bread(dev, IBLOCK(inum, sb));

dip = (struct dinode *)bp->data + inum % IPB; // 遍历该buffer中所有inode

if (dip->type == 0)

{ // a free inode

memset(dip, 0, sizeof(*dip));

dip->type = type;

log_write(bp); // mark it allocated on the disk

brelse(bp);

return iget(dev, inum);

}

brelse(bp);

}

panic("ialloc: no inodes");

}

ialloc()用于返回一个空闲的inode,通过遍历得到dip->type = 0的inode的inum,有了inum就可以通过iget()得到inode。

iget():

// Find the inode with number inum on device dev

// and return the in-memory copy. Does not lock

// the inode and does not read it from disk.

// 从inode cache 中获得inode

static struct inode *

iget(uint dev, uint inum)

{

struct inode *ip, *empty;

acquire(&icache.lock);

// Is the inode already cached?

empty = 0;

for (ip = &icache.inode[0]; ip < &icache.inode[NINODE]; ip++)

{

// 对应inum的inode就在cache中

if (ip->ref > 0 && ip->dev == dev && ip->inum == inum)

{

ip->ref++;

release(&icache.lock);

return ip;

}

// 不在则将ip->ref == 0的inode替换掉

if (empty == 0 && ip->ref == 0) // Remember empty slot.

empty = ip;

}

// Recycle an inode cache entry.

if (empty == 0)

panic("iget: no inodes");

ip = empty;

ip->dev = dev;

ip->inum = inum;

ip->ref = 1;

ip->valid = 0;

release(&icache.lock);

return ip;

}

和buffer cache一样,为了限制inode的数量和支持并发,我们使用的所有的inode也都属于inode cache。

iupdate():

// Copy a modified in-memory inode to disk.

// Must be called after every change to an ip->xxx field

// that lives on disk, since i-node cache is write-through.

// Caller must hold ip->lock.

// 更新Inode(一旦ip->xxx改变就要调用)

void iupdate(struct inode *ip)

{

struct buf *bp;

struct dinode *dip;

bp = bread(ip->dev, IBLOCK(ip->inum, sb));

dip = (struct dinode *)bp->data + ip->inum % IPB;

dip->type = ip->type;

dip->major = ip->major;

dip->minor = ip->minor;

dip->nlink = ip->nlink;

dip->size = ip->size;

memmove(dip->addrs, ip->addrs, sizeof(ip->addrs));

log_write(bp);

brelse(bp);

}

更新inode的内容,将in-memory inode写入on-disk memory inode,并更新磁盘上对应的inode

iput():

// Drop a reference to an in-memory inode.

// If that was the last reference, the inode cache entry can

// be recycled.

// If that was the last reference and the inode has no links

// to it, free the inode (and its content) on disk.

// All calls to iput() must be inside a transaction in

// case it has to free the inode.

// Inode ip的ref--,如果是最后一个的话并且link=0则将此Inode(文件)删除掉

void iput(struct inode *ip)

{

acquire(&icache.lock);

if (ip->ref == 1 && ip->valid && ip->nlink == 0)

{

// 删除文件

// ip->ref == 1意味着这是最后一个引用该Inode的地方,注意并没有删除掉对应的block里的内容,而是将Inode清空

// inode has no links and no other references: truncate and free.

// ip->ref == 1 means no other process can have ip locked,

// so this acquiresleep() won't block (or deadlock).

acquiresleep(&ip->lock);

release(&icache.lock);

itrunc(ip); //

ip->type = 0;

iupdate(ip);

ip->valid = 0;

releasesleep(&ip->lock);

acquire(&icache.lock);

}

ip->ref--;

release(&icache.lock);

}

iput()负责ref–,前面我们提到ref指的是进程打开文件的次数,所以iput()也只会在类似关闭文件的场合用到。不仅如此,这里还包含了一种情况:ref=0 && nlink=0,即没有任何一个进程或者目录引用它,这不就相当于文件的删除吗。我们来看看xv6是怎么进行文件删除操作的。

itrunc():

// Truncate inode (discard contents).

// Only called when the inode has no links

// to it (no directory entries referring to it)

// and has no in-memory reference to it (is

// not an open file or current directory).

// 释放掉Inode ip的所有addr[](将addr[]清0,不会将指向的block释放掉)

static void

itrunc(struct inode *ip)

{

int i, j, j2;

struct buf *bp, *bp2;

uint *a, *a2;

for (i = 0; i < NDIRECT; i++)

{

if (ip->addrs[i])

{

bfree(ip->dev, ip->addrs[i]);

ip->addrs[i] = 0;

}

}

if (ip->addrs[NDIRECT])

{

bp = bread(ip->dev, ip->addrs[NDIRECT]);

a = (uint *)bp->data;

for (j = 0; j < NINDIRECT; j++)

{

if (a[j])

bfree(ip->dev, a[j]);

}

brelse(bp);

bfree(ip->dev, ip->addrs[NDIRECT]);

ip->addrs[NDIRECT] = 0;

}

if (ip->addrs[NDIRECT + 1])

{

bp = bread(ip->dev, ip->addrs[NDIRECT + 1]);

a = (uint *)bp->data;

for (j = 0; j < NINDIRECT; j++)

{

if (a[j])

{

bp2 = bread(ip->dev, a[j]);

a2 = (uint *)bp2->data;

for (j2 = 0; j2 < NINDIRECT; j2++)

{

if (a2[j2])

bfree(ip->dev, a2[j2]);

}

brelse(bp2);

bfree(ip->dev, a[j]);

}

}

brelse(bp);

bfree(ip->dev, ip->addrs[NDIRECT + 1]);

ip->addrs[NDIRECT + 1] = 0;

}

ip->size = 0;

iupdate(ip);

}

我们只有看第一处for循环就能明白它的大概原理。xv6的删除文件就是释放掉inode所有的addr,将其清0,而没有把它对应的block清0。这么做的原因有两点:我们的文件本质上就是inode,inode负责索引data,inode没了就相当于文件删除了,block留在磁盘中也不会有影响;可能还会有别的inode引用该block,贸然删除肯定不行。

readi():

// Read data from inode.

// Caller must hold ip->lock.

// If user_dst==1, then dst is a user virtual address;

// otherwise, dst is a kernel address.

// 从Inode中读数据到dst中,off:文件偏移位置,n:总长度

int readi(struct inode *ip, int user_dst, uint64 dst, uint off, uint n)

{

uint tot, m;

struct buf *bp;

if (off > ip->size || off + n < off)

return -1;

if (off + n > ip->size)

n = ip->size - off;

for (tot = 0; tot < n; tot += m, off += m, dst += m)

{

bp = bread(ip->dev, bmap(ip, off / BSIZE));

m = min(n - tot, BSIZE - off % BSIZE);

if (either_copyout(user_dst, dst, bp->data + (off % BSIZE), m) == -1)

{

brelse(bp);

break;

}

brelse(bp);

}

return n;

}

// Write data to inode.

// Caller must hold ip->lock.

// If user_src==1, then src is a user virtual address;

// otherwise, src is a kernel address.

int writei(struct inode *ip, int user_src, uint64 src, uint off, uint n)

{

uint tot, m;

struct buf *bp;

if (off > ip->size || off + n < off)

return -1;

if (off + n > MAXFILE * BSIZE)

return -1;

for (tot = 0; tot < n; tot += m, off += m, src += m)

{

bp = bread(ip->dev, bmap(ip, off / BSIZE));

m = min(n - tot, BSIZE - off % BSIZE);

if (either_copyin(bp->data + (off % BSIZE), user_src, src, m) == -1)

{

brelse(bp);

break;

}

log_write(bp);

brelse(bp);

}

if (n > 0)

{

if (off > ip->size)

ip->size = off;

// write the i-node back to disk even if the size didn't change

// because the loop above might have called bmap() and added a new

// block to ip->addrs[].

iupdate(ip);

}

return n;

}

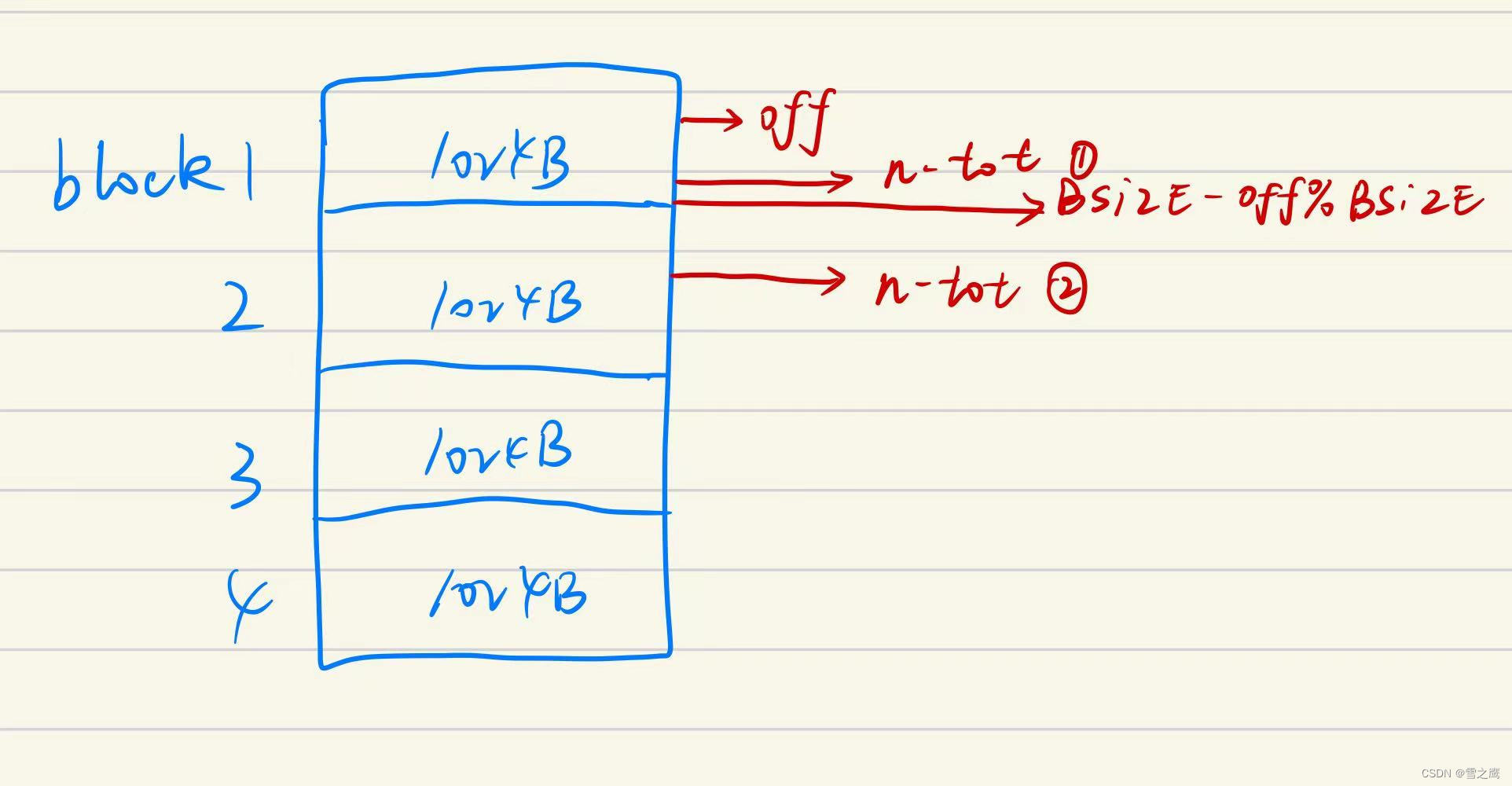

readi()和writei()结构相似,我们只分析readi(), m = min(n - tot, BSIZE - off % BSIZE)实际上是将一次读分成了两种情况:如果这次读的长度n没有超过当前block,则直接读出n-tot长度的数据即可;如果超过了当前block,则需要分多次读(因为我们每次最多读1个block)。

至此,inode层完成,我们的“文件”也形成了。只要我们知道某一文件的Inode号,我们就可以进行文件的读写操作。当然现实的文件系统没有这么不“智能”,接下来我们还要给文件起名字,实现路径等功能。

Directory

Directory层(fs.c)的主要作用:

- Directory:将每个目录实现为一种特殊的Inode,把文件命名和Inode绑定

Directory其实也是文件,因为它和文件一样,都是inode。唯一的不同就是,普通文件存储的是data,而它存储的是dirent(目录)。

struct dirent

{

ushort inum;

char name[DIRSIZ];

};

目录里面存的就是dirent这个结构体,它很简单和直观,靠1个inum和1个文件名完成文件名到inode的映射,相当于我们只要找到对应目录下的文件名就能找到对应的Inode,文件系统“智能”起来了。

dirlookup():

// Look for a directory entry in a directory.

// If found, set *poff to byte offset of entry.

// 在目录中根据名字找到文件,返回Inode

struct inode *

dirlookup(struct inode *dp, char *name, uint *poff)

{

uint off, inum;

struct dirent de;

if (dp->type != T_DIR)

panic("dirlookup not DIR");

for (off = 0; off < dp->size; off += sizeof(de)) // 遍历该目录下的所有名字,然后匹配

{

if (readi(dp, 0, (uint64)&de, off, sizeof(de)) != sizeof(de))

panic("dirlookup read");

if (de.inum == 0)

continue;

if (namecmp(name, de.name) == 0)

{

// entry matches path element

if (poff)

*poff = off;

inum = de.inum;

return iget(dp->dev, inum);

}

}

return 0;

}

dirlookup()负责查找目录dp下的与name匹配的文件,找到直接返回对应inode号。查找的方式也很直接:遍历当前目录下的所有文件,知道name出现为止。

dirlink():

// Write a new directory entry (name, inum) into the directory dp.

int dirlink(struct inode *dp, char *name, uint inum)

{

int off;

struct dirent de;

struct inode *ip;

// Check that name is not present.

if ((ip = dirlookup(dp, name, 0)) != 0)

{

iput(ip);

return -1;

}

// Look for an empty dirent.

for (off = 0; off < dp->size; off += sizeof(de))

{

if (readi(dp, 0, (uint64)&de, off, sizeof(de)) != sizeof(de))

panic("dirlink read");

if (de.inum == 0)

break;

}

strncpy(de.name, name, DIRSIZ); // de.name

de.inum = inum; // de.inum

if (writei(dp, 0, (uint64)&de, off, sizeof(de)) != sizeof(de))

panic("dirlink");

return 0;

}

dirlink()负责把指定文件inum写入到目录dp中,命名为name。

Pathname

Pathname层(fs.c)的主要作用:

- Pathname:提供路径功能

实现了文件命名的功能后,再看看现在的文件系统,还差一个路径的功能,即目录可以一层套一层,每一个文件或目录都有一个路径。

skipelem():

// Copy the next path element from path into name.

// Return a pointer to the element following the copied one.

// The returned path has no leading slashes,

// so the caller can check *path=='\0' to see if the name is the last one.

// If no name to remove, return 0.

//

// Examples:

// skipelem("a/bb/c", name) = "bb/c", setting name = "a"

// skipelem("///a//bb", name) = "bb", setting name = "a"

// skipelem("a", name) = "", setting name = "a"

// skipelem("", name) = skipelem("////", name) = 0

//

static char *

skipelem(char *path, char *name)

{

char *s;

int len;

while (*path == '/')

path++;

if (*path == 0)

return 0;

s = path;

while (*path != '/' && *path != 0)

path++;

len = path - s;

if (len >= DIRSIZ)

memmove(name, s, DIRSIZ);

else

{

memmove(name, s, len);

name[len] = 0;

}

while (*path == '/')

path++;

return path;

}

skipelem()函数主要是为后面的namex()函数做准备,功能是把路径拆开。比如路径path=“a/bb/c”,它会把第一级路径名赋值给name,剩下的路径名返回,所以name=a, return=bb/c

namex():

// Look up and return the inode for a path name.

// If parent != 0, return the inode for the parent and copy the final

// path element into name, which must have room for DIRSIZ bytes.

// Must be called inside a transaction since it calls iput().

static struct inode *

namex(char *path, int nameiparent, char *name)

{

struct inode *ip, *next;

if (*path == '/')

ip = iget(ROOTDEV, ROOTINO); // 根目录

else

ip = idup(myproc()->cwd); // 当前Inode,即进程当前在哪一个目录下

while ((path = skipelem(path, name)) != 0) // path=0表示末尾,不能再递归遍历了

{

ilock(ip);

if (ip->type != T_DIR)

{

iunlockput(ip);

return 0;

}

if (nameiparent && *path == '\0') // path=0表示末尾,不能再递归遍历了

{

// Stop one level early.

iunlock(ip);

return ip;

}

if ((next = dirlookup(ip, name, 0)) == 0)

{

iunlockput(ip);

return 0;

}

iunlockput(ip);

ip = next; // 递归查找

}

if (nameiparent)

{

iput(ip);

return 0;

}

return ip;

}

namx()会根据路径名path返回对应文件的inode,在dirlookup()的基础上完成了路径功能。忽略nameiparent, while ((path = skipelem(path, name)) != 0)将path一级一级地分解,得到的name作为dirlookup()的参数,如此循环,最后得到我们需要的inode

File descriptor

File descriptor层(file.c)的主要作用:

- File descriptor:抽象了管道、设备、文件等资源, 即一切皆文件

我们经常所说的一切皆文件,就是在File descriptor层实现的。在这里我们只拿里面的fileread()函数作为一个例子解释,看看代码是如何做到管道、设备、文件的抽象。

sys_read():

uint64

sys_read(void)

{

struct file *f;

int n;

uint64 p;

if (argfd(0, 0, &f) < 0 || argint(2, &n) < 0 || argaddr(1, &p) < 0)

return -1;

return fileread(f, p, n);

}

// Fetch the nth word-sized system call argument as a file descriptor

// and return both the descriptor and the corresponding struct file.

static int

argfd(int n, int *pfd, struct file **pf)

{

int fd;

struct file *f;

if (argint(n, &fd) < 0)

return -1;

if (fd < 0 || fd >= NOFILE || (f = myproc()->ofile[fd]) == 0)

{

printf("f = %d,fd = %d", f, fd);

return -1;

}

if (pfd)

*pfd = fd;

if (pf)

*pf = f;

return 0;

}

首先从read的系统调用开始,文件描述符fd会作为read的参数传入,通过argfd()解析出对应的file,

f = myproc()->ofile[fd]也解释了fd和file的关系。

fileread():

// Read from file f.

// addr is a user virtual address.

int fileread(struct file *f, uint64 addr, int n)

{

int r = 0;

if (f->readable == 0)

return -1;

if (f->type == FD_PIPE)

{

r = piperead(f->pipe, addr, n);

}

else if (f->type == FD_DEVICE)

{

if (f->major < 0 || f->major >= NDEV || !devsw[f->major].read)

return -1;

r = devsw[f->major].read(f, 1, addr, n);

}

else if (f->type == FD_INODE)

{

ilock(f->ip);

if ((r = readi(f->ip, 1, addr, f->off, n)) > 0)

f->off += r;

iunlock(f->ip);

}

else

{

panic("fileread");

}

return r;

}

抽象的方法是通过f->type来判断文件的类型,不同类型执行不同的操作。

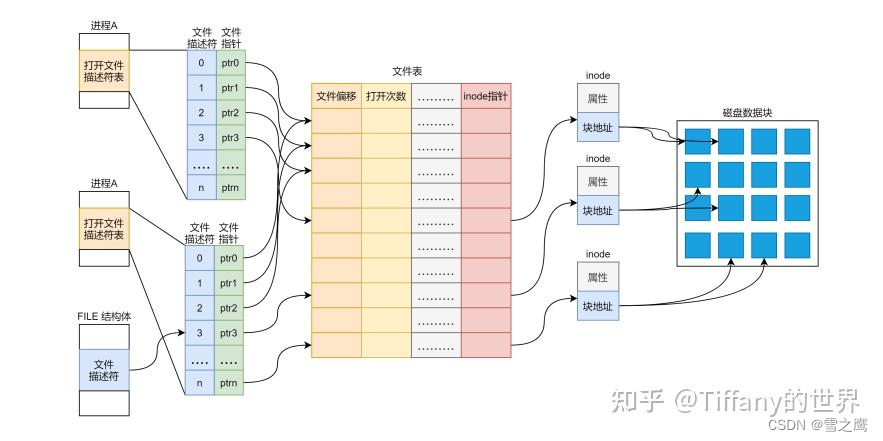

整体结构可以参考这张图:

就像buffer cache,inode cache,为了限制数量和支持并发,内核会维护一张文件表,所有的file都属于这个文件表。每个进程都拥有一个属于自己的ofile,用于记录打开的文件,使用文件描述符fd来索引相应的文件。

struct

{

struct spinlock lock;

struct file file[NFILE];

} ftable;

浙公网安备 33010602011771号

浙公网安备 33010602011771号