Water issues in China

Introduction of rural industrial water pollution in China

Water supply and quality are fundamental issues in China. A few years ago, the debate about who will feed China emphasised scarcity of farmland and the food crisis (Brown, 1995). Yet the most critical resource in China is not land or food, but water (as Brown later (2001) came to recognise). Not only are per capita water resources limited (Niu and Harris, 1996) and the spatial distribution of water resources extremely uneven, there is also significant waste of water. This waste is related to inefficient irrigation practices, leaking water pipes, and water pollution. Growing municipal and industrial waste discharges, coupled with limited wastewater treatment capacity, are the principal drivers of water pollution. About two-thirds of the total waste discharge into rivers, lakes and the sea derives from industry, and about 80% of that is untreated. Most of the untreated discharge comes from rural industries.

Rural industries stand out as one of the most spectacular respondents to China's 1978 economic reform. They represent a middle ground between private and state ownership and have not developed in any other country on such a large scale and at such a rapid rate. They have become the driving force behind China's economic growth and a significant engine of China's transition, with double-digit growth rates since the late 1970s. To a large degree, this growth of rural industry was neither planned nor anticipated (Bruton et al., 2000).

However, the environmental cost of China's rural industrialisation is enormous. Rural industry consumes massive quantities of water and pollutes a large proportion of rural water bodies (Anid and Tschirley, 1998; Wheeler et al., 2000). While a few large rural enterprises have advanced technology and sophisticated wastewater treatment facilities, rural enterprises are characterised by their small scale, outmoded technology, obsolete equipment, poor management and heavy consumption of water resources (Qu and Li, 1994). As a result, water pollution is a serious problem wherever there are rural industries. Over 80% of China's rivers have some degree of contamination (Qi et al., 1999). China's 2002 State of the Environment Report shows that 70% of the 741 river sections monitored were unfit for human contact (pollutions levels at or above Grade IV standard) (SEPA, 2002). The most polluted was the Hai River, where 86% of monitored sections were unfit for human contact.

China's environmental policy is widely considered as a comparatively success in urban areas, with marked declines in urban pollution (Florig et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 1997; Abigail, 1997). However, these efforts rarely reach the rural areas, where environmental policy is not effective (Florig et al., 1995; Zhang et al., 1997; Abigail, 1997). One of the names for this phenomenon is a policy ‘implementation gap’ (Chan et al., 1995). It is the aim of this paper to understand the reasons for this implementation gap. Previous studies have attributed it to a combination of factors, including legislative shortcomings, poorly designed policy instruments, an unsupportive work environment for environmental regulators, and a pro-growth political and social environment (Chan et al., 1995; Wong and Hon, 1994; Ross, 1992). These are important; however, we argue that the most fundamental factors causing rural water pollution are the very same factors that have underpinned the economic success of rural industry. The problem of water pollution, we argue, is therefore unlikely to be remedied by discrete institutional changes, and instead requires a transformation of the models associated with rural development.

Rural industrialisation

The rise of rural industry is one of the outcomes of China's transition. The rural household responsibility system introduced in the late 1970s released hundreds of millions of peasants from the farming sector. To accommodate increasing under- and unemployment in China's countryside, the central government allowed industrial development in rural areas (Lin, 1997; Oi, 1995; Lieberthal, 1995). Peasants were encouraged “to leave the land but not the village” (litu bu lixiang in Chinese) (Tan, 1993

Rural industry and the water crisis

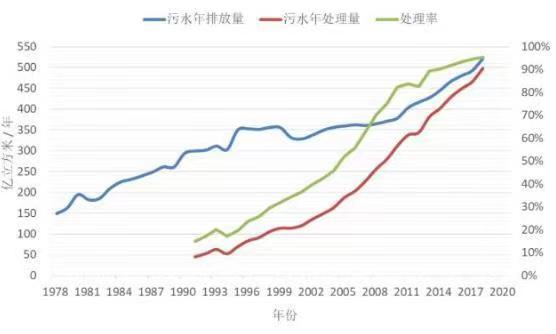

Rural industries have been widely criticised for their waste of natural resources, including water resources, due to substandard equipment and basic technology (Shen et al., 2005; Edmonds, 1994; Wong, 1999). Most rural industries have no wastewater or hazardous waste treatment facilities. Almost all wastewater is directly discharged into local river systems. According to the State Environmental Protection Agency (SEPA, 2002), the total discharge of sewage and wastewater in China was 62 billion

Small is not beautiful

One of the common characteristics of rural industry is small enterprises. The mushrooming Chinese economy allows a few small rural enterprises to become large and some successful rural enterprises have grown to employ well over 1000 workers. Likewise, those rural enterprises registered as foreign or Hong Kong/Macau/Taiwan owned employed on average over 130 workers (Table 1). Nevertheless, the average size of all rural enterprises was only six employees in 2003. In fact, more than 93% of all the

Institutional framework

The factors identified in the previous section only partially explain the problem of environmental enforcement. The national environmental protection system is also a significant factor. When the reform program was introduced in 1978, the central Chinese government also introduced a legal framework for environmental protection and, as mentioned above, tough punishments are stipulated in the laws for violating environmental regulations. Since 1978, many water pollution laws have been issued

Administrative transition

We have already claimed that the factors that underpin water pollution among TVEs are also the factors that have helped TVEs become so important: in that respect, water pollution is integral to the model of TVE growth. But Section 5 demonstrated some institutional weaknesses that prevent the complete regulation of rural industry by the state's environmental protection system. To a large degree, these weaknesses reflect the character of the transition in China.

Conclusion

Rural industrial growth in China has occurred almost outside central environmental management systems. Despite a variety of new laws, regulations and guidelines, implementation gaps still exist. The current water pollution control system relies on a top-down approach to monitoring, control and supervision. While this may work in cities where industries are spatially concentrated and pollution-monitoring systems are well developed, it does not work in the rural areas where water polluting

浙公网安备 33010602011771号

浙公网安备 33010602011771号