Python自然语言处理学习笔记(3):1.1 语言计算:文本和单词

新手上路,翻译不恰之处,恳请指出,不胜感谢![]()

Updated log

1st:2011/8/5

2nd:2011/8/6

3rd:2012/5/14

每次按一小节来分,本篇涉及第一章的1.1,除了最后的小节&扩展阅读&习题放在一篇博客内。

CHAPTER 1 第一章

Language Processing and Python 语言处理和Python

It is easy to get our hands on millions of words of text. What can we do with it, assuming we can write some simple programs? In this chapter, we’ll address the following questions:

我们可以轻松地获得上百万字的文本。假设我们会写一些简单的程序 ,那我们可以对它来做些什么呢?本章我们将解决以下几个问题:

1. What can we achieve by combining simple programming techniques with large quantities of text?

通过简单的编程技术对大量的文本合并,我们能实现什么?

2. How can we automatically extract key words and phrases that sum up the style and content of a text?

我们如何自动地提取关键字和词组来总结文本的风格和内容?

3. What tools and techniques does the Python programming language provide for such work?

Python编程语言为这些工作提供了什么工具和技术?

4. What are some of the interesting challenges of natural language processing?

自然语言处理有哪些有趣的挑战呢?

This chapter is divided into sections that skip between two quite different styles. In the“computing with language” sections, we will take on some linguistically motivated programming tasks(语言相关的编程任务) without necessarily explaining how they work. In the “closer look at Python” sections we will systematically review key programming concepts. We’ll flag(标志) the two styles in the section titles, but later chapters will mix both styles without being so up-front (显著的)about it. We hope this style of introduction gives you an authentic taste(原味) of what will come later, while covering a range of elementary concepts in linguistics and computer science. If you have basic familiarity with both areas, you can skip to Section 1.5; we will repeat any important points in later chapters, and if you miss anything you can easily consult the online reference material at http://www.nltk.org/. If the material is completely new to you, this chapter will raise more questions than it answers, questions that are addressed in the rest of this book.

本章分为完全不同风格的两部分。 在 “ 语言计算 ” 部分,我们将进行一些语言相关的编程任务而不去解释它们是如何实现的。 在 “ 细看Python ” 部分 , 我们将系统地回顾关键的编程概念 。 我们 使用章节标题来区分这两种风格,而后面几章将混合两种风格而不作明显地区分。我们希望这种介绍方式可以使你对接下来将要接触的内容有一个真实的体味 ,与此同时,涵盖语言学与计算机科学的基本概念。如果你对这两个方面已经有了基本的了解,可以跳到 1.5 节。我们将在后续的章节中重复所有要点,如果错过了什么 , 你可以很容易地在 http://www.nltk.org/ 上查询在线参考材料。如果这些材料对你而言是全新的,那么本章将产生的问题比它所解答的问题更多,这些问题将在本书的其余部分讨论。

1.1 Computing with Language: Texts and Words 语言计算:文本和单词

We’re all very familiar with text, since we read and write it every day. Here we will treat text as raw data for the programs we write, programs that manipulate and analyze it in a variety of interesting ways. But before we can do this, we have to get started with the Python interpreter.

我们都对文本非常熟悉,因为我们每天都进行阅读和写作。 在这里 ,我们将文本作为我们编写的程序的原始数据,我们将以很多有趣的编程方式来处理和分析文本。但在我们能能进行这些工作前,我们必须得从 Python 解释器开始。

Getting Started with Python Python入门(不会Python的童鞋,去找本入门的书看看,上手很快)

One of the friendly things about Python is that it allows you to type directly into the interactive interpreter—the program that will be running your Python programs. You can access the Python interpreter using a simple graphical interface called the Interactive DeveLopment Environment (IDLE). On a Mac you can find this under Applications→MacPython, and on Windows under All Programs→Python. Under Unix you can run Python from the shell by typing idle (if this is not installed, try typing python). The interpreter will print a blurb about your Python version; simply check that you are running Python 2.4 or 2.5 (here it is 2.5.1):

Python 对用户友好的一个特性是你可以在交互式解释器直接输入代码—— 解释器将运行你的Python程序。你可以通过一个称为交互式开发环境( Interactive DeveLopment Environment,简称IDLE)的简单图形接口来访问 Python 解释器。在Mac上,你可以在“ 应用程序 → MacPython ”中找到;在 Windows 中,你可以在“ 程序 → Python ” 中找到。在Unix 下,你可以在 shell 输入“ idle ”来运行 Python(如果没有安装,尝试输入 python )。解释器将会输入关于你的 Python 的版本简介,请检查你是否运行在 Python 2.4 或 2.5 (这里是2.5.1,个人推荐大家用2.7,老库基本可用) :

[GCC 4.0.1 (Apple Inc. build 5465)] on darwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>

The >>> prompt indicates that the Python interpreter is now waiting for input. When copying examples from this book, don’t type the “>>>” yourself. Now, let’s begin by using Python as a calculator:

>>>1+5*2-3

8

>>>

Once the interpreter has finished calculating the answer and displaying it, the prompt reappears. This means the Python interpreter is waiting for another instruction.

![]() Your Turn: Enter a few more expressions of your own. You can use asterisk (*) for multiplication and slash (/) for division, and parentheses for bracketing expressions. Note that division doesn’t always behave as you might expect—it does integer division (with rounding of fractions downwards) when you type 1/3 and “floating-point” (or decimal) division when you type 1.0/3.0. In order to get the expected behavior of division (standard in Python 3.0), you need to type: from __future__import division. Python中/是整除,要用真正的除法可用以上两种办法

Your Turn: Enter a few more expressions of your own. You can use asterisk (*) for multiplication and slash (/) for division, and parentheses for bracketing expressions. Note that division doesn’t always behave as you might expect—it does integer division (with rounding of fractions downwards) when you type 1/3 and “floating-point” (or decimal) division when you type 1.0/3.0. In order to get the expected behavior of division (standard in Python 3.0), you need to type: from __future__import division. Python中/是整除,要用真正的除法可用以上两种办法

The preceding examples demonstrate how you can work interactively with the Python interpreter, experimenting with various expressions in the language to see what they do. Now let’s try a non-sensical (无意义的)expression to see how the interpreter handles it:

>>>1+

File "<stdin>", line 1

1+

^

SyntaxError: invalid syntax

>>>

This produced a syntax error. In Python, it doesn’t make sense to end an instruction with a plus sign. The Python interpreter indicates the line where the problem occurred (line 1 of <stdin>, which stands for “standard input”).

Now that we can use the Python interpreter, we’re ready to start working with language data.

Getting Started with NLTK 准备开始NLTK

Before going further you should install NLTK, downloadable for free from http://www.nltk.org/. Follow the instructions there to download the version required for your platform.

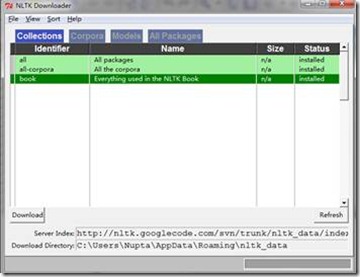

Once you’ve installed NLTK, start up the Python interpreter as before, and install the data required for the book by typing the following two commands at the Python prompt, then selecting the book collection as shown in Figure 1-1

>>> nltk.download()

我这个会有警告信息,不过没事:

Warning (from warnings module):

File "C:\Python26\lib\site-packages\nltk\__init__.py", line 588

DeprecationWarning: object.__new__() takes no parameters

Figure 1-1. Downloading the NLTK Book Collection: Browse the available packages using nltk.download(). The Collections tab on the downloader shows how the packages are grouped into sets, and you should select the line labeled book to obtain all data required for the examples and exercises in this book. It consists of about 30 compressed files requiring about 100Mb disk space. The full collection of data (i.e., all in the downloader) is about five times this size (at the time of writing) and continues to expand. 此图是我自己截的,不是原图。

Once the data is downloaded to your machine, you can load some of it using the Python interpreter. The first step is to type a special command at the Python prompt, which tells the interpreter to load some texts for us to explore: from nltk.book import *. This says “from NLTK’s book module, load all items.” The book module contains all the data you will need as you read this chapter. After printing a welcome message, it loads the text of several books (this will take a few seconds). Here’s the command again, together with the output that you will see. Take care to get spelling and punctuation(标点符号) right, and remember that you don’t type the >>>.

Loading text1, ..., text9 and sent1, ..., sent9

Type the name of the text or sentence to view it.

Type: 'texts()' or 'sents()' to list the materials.

text1: Moby Dick by Herman Melville 1851

text2: Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen 1811

text3: The Book of Genesis

text4: Inaugural Address Corpus

text5: Chat Corpus

text6: Monty Python and the Holy Grail

text7: Wall Street Journal

text8: Personals Corpus

text9: The Man Who Was Thursday by G . K . Chesterton 1908

>>>

Any time we want to find out about these texts, we just have to enter their names at the Python prompt:

>>> text1

<Text: Moby Dick by Herman Melville 1851>

>>> text2

<Text: Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen 1811>

>>>

Now that we can use the Python interpreter, and have some data to work with, we’re ready to get started. 要开始了!

Searching Text 搜索文本

There are many ways to examine the context of a text apart from(除了) simply reading it. A concordance(主要词语索引) view shows us every occurrence of a given word, together with some context. Here we look up the word monstrous(巨大的) in Moby Dick(白鲸记) by entering text1 followed by a period, then the term concordance, and then placing "monstrous" in parentheses(圆括号):

>>> text1.concordance("monstrous")

Your Turn: Try searching for other words; to save re-typing, you might be able to use up-arrow, Ctrl-up-arrow, or Alt-p to access the previous command and modify the word being searched. You can also try searches on some of the other texts we have included. For example, search Sense and Sensibility(理智与情感) for the word affection(感情), using text2.concordance("affection"). Search the book of Genesis to find out how long some people lived, using: text3.concordance("lived"). You could look at text4, the Inaugural Address(就职演说) Corpus, to see examples of English going back to 1789, and search for words like nation, terror, god, to see how these words have been used differently over time. We’ve also included text5, the NPS Chat Corpus: search this for unconventional words like im, ur, lol. (Note that this corpus is uncensored(未经审查的)!) PS:那个聊天语料库,可以搜好多东西,例如…

Your Turn: Try searching for other words; to save re-typing, you might be able to use up-arrow, Ctrl-up-arrow, or Alt-p to access the previous command and modify the word being searched. You can also try searches on some of the other texts we have included. For example, search Sense and Sensibility(理智与情感) for the word affection(感情), using text2.concordance("affection"). Search the book of Genesis to find out how long some people lived, using: text3.concordance("lived"). You could look at text4, the Inaugural Address(就职演说) Corpus, to see examples of English going back to 1789, and search for words like nation, terror, god, to see how these words have been used differently over time. We’ve also included text5, the NPS Chat Corpus: search this for unconventional words like im, ur, lol. (Note that this corpus is uncensored(未经审查的)!) PS:那个聊天语料库,可以搜好多东西,例如…

Once you’ve spent a little while examining these texts, we hope you have a new sense of the richness and diversity(丰富性和多样性) of language. In the next chapter you will learn how to access a broader range of text, including text in languages other than English.

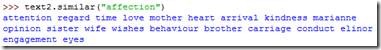

A concordance permits us to see words in context. For example, we saw that monstrous occurred in contexts such as the ___ pictures and the ___ size. What other words appear in a similar range of contexts(出现在本文中类似的范围)? We can find out by appending the term similar to the name of the text in question, then inserting the relevant word in parentheses:

>>> text1.similar("monstrous")

Observe that we get different results for different texts. Austen(奥斯丁,英国女小说家) uses this word quite differently from Melville; for her, monstrous has positive connotations(正面的涵义), and sometimes functions as an intensifier(强调成分) like the word very.

The term common_contexts allows us to examine just the contexts that are shared by two or more words, such as monstrous and very. We have to enclose these words by square brackets(方括号) as well as parentheses, and separate them with a comma:

>>> text2.common_contexts(["monstrous", "very"])

be_glad am_glad a_pretty is_pretty a_lucky

>>>

Figure 1-2. Lexical dispersion plot(词汇分离图) for words in U.S. Presidential Inaugural Addresses: This can be used to investigate changes in language use over time

Your Turn: Pick another pair of words and compare their usage in two different texts, using the similar() and common_contexts() functions.

Your Turn: Pick another pair of words and compare their usage in two different texts, using the similar() and common_contexts() functions.

It is one thing to automatically detect that a particular word occurs in a text, and to display some words that appear in the same context. However, we can also determine the location of a word in the text: how many words from the beginning it appears. This positional information can be displayed using a dispersion plot(离散图). Each stripe(条纹) represents an instance of a word, and each row represents the entire text. In Figure 1-2 we see some striking(显著的) patterns of word usage over the last 220 years (in an artificial text constructed by joining the texts of the Inaugural Address Corpus end-to-end(首尾相连)). You can produce this plot as shown below. You might like to try more words (e.g., liberty, constitution) and different texts. Can you predict the dispersion of a word before you view it? As before, take care to get the quotes, commas, brackets, and parentheses exactly right.

>>> text4.dispersion_plot(["citizens", "democracy", "freedom", "duties", "America"])

>>>

Important: You need to have Python’s NumPy and Matplotlib packages installed in order to produce the graphical plots used in this book. Please see http://www.nltk.org/ for installation instructions.

Important: You need to have Python’s NumPy and Matplotlib packages installed in order to produce the graphical plots used in this book. Please see http://www.nltk.org/ for installation instructions.

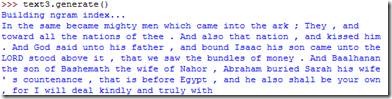

Now, just for fun, let’s try generating some random text in the various styles we have just seen. To do this, we type the name of the text followed by the term generate. (We need to include the parentheses, but there’s nothing that goes between them.)

>>> text3.generate()

Note that the first time you run this command, it is slow because it gathers statistics about word sequences. Each time you run it, you will get different output text. Now try generating random text in the style of an inaugural address or an Internet chat room. Although the text is random, it reuses common words and phrases from the source text and gives us a sense of its style and content. (What is lacking in this randomly generated text?在这种随机产生的文本中缺点是什么?我觉得是看不懂文本的内容)

When generate produces its output, punctuation is split off from the preceding word. While this is not correct formatting for English text, we do it to make clear that words and punctuation are independent of one another. You will learn more about this in Chapter 3.

When generate produces its output, punctuation is split off from the preceding word. While this is not correct formatting for English text, we do it to make clear that words and punctuation are independent of one another. You will learn more about this in Chapter 3.

Counting Vocabulary 词汇计数

The most obvious fact about texts that emerges from the preceding examples is that they differ in the vocabulary they use. In this section, we will see how to use the computer to count the words in a text in a variety of useful ways. As before, you will jump right in(马上投入) and experiment with the Python interpreter, even though you may not have studied Python systematically yet. Test your understanding by modifying the examples, and trying the exercises at the end of the chapter.

Let’s begin by finding out the length of a text from start to finish, in terms of the words and punctuation symbols that appear. We use the term len to get the length of something, which we’ll apply here to the book of Genesis:

>>> len(text3)

44764

>>>

So Genesis has 44,764 words and punctuation symbols, or “tokens.” A token is the technical name for a sequence of characters(标记是表示一个字符序列的术语)—such as hairy, his, or :)—that we want to treat as a group. When we count the number of tokens in a text, say, the phrase to be or not to be, we are counting occurrences of these sequences. Thus, in our example phrase there are two occurrences of to, two of be, and one each of or and not. But there are only four distinct vocabulary items in this phrase. How many distinct words does the book of Genesis contain? To work this out in Python, we have to pose(提出) the question slightly differently. The vocabulary of a text is just the set of tokens that it uses, since in a set, all duplicates are collapsed together. In Python we can obtain the vocabulary items of text3 with the command: set(text3). When you do this, many screens of words will fly past. Now try the following:

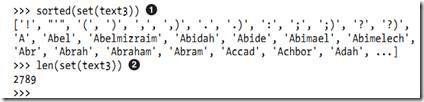

By wrapping sorted() around the Python expression set(text3)① , we obtain a sorted list of vocabulary items, beginning with various punctuation symbols and continuing with words starting with A. All capitalized words precede lowercase words(大写单词排在小写单词前面). We discover the size of the vocabulary indirectly, by asking for the number of items in the set, and again we can use len to obtain this number②. Although it has 44,764 tokens, this book has only 2,789 distinct words, or “word types.” A word type is the form or spelling of the word independently of its specific occurrences in a text—that is, the word considered as a unique item of vocabulary. Our count of 2,789 items will include punctuation symbols, so we will generally call these unique items types instead of word types.

Now, let’s calculate a measure of the lexical richness of the text(文本词汇丰富度的测量). The next example shows us that each word is used 16 times on average (we need to make sure Python uses floating-point division):

>>> len(text3) / len(set(text3))

16.050197203298673

>>>

Next, let’s focus on particular words. We can count how often a word occurs in a text, and compute what percentage of the text is taken up(占据) by a specific word:

>>> text3.count("smote")

5

>>>100* text4.count('a') / len(text4)

1.4643016433938312

>>>

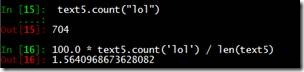

Your Turn: How many times does the word lol appear in text5? How much is this as a percentage of the total number of words in this text?

Your Turn: How many times does the word lol appear in text5? How much is this as a percentage of the total number of words in this text?

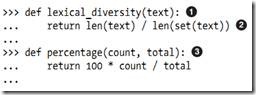

You may want to repeat such calculations on several texts, but it is tedious to keep retyping the formula. Instead, you can come up with your own name for a task, like “lexical_diversity” or “percentage”, and associate it with a block of code. Now you only have to type a short name instead of one or more complete lines of Python code, and you can reuse it as often as you like. The block of code that does a task for us is called a function, and we define a short name for our function with the keyword def. The next example shows how to define two new functions, lexical_diversity() and percentage():

In the definition of lexical diversity()①, we specify a parameter labeled text. This parameter is a “placeholder”(占位符)for the actual text whose lexical diversity we want to compute, and reoccurs in the block of code that will run when the function is used, in line②. Similarly, percentage()③is defined to take two parameters, labeled count and total .

>>> lexical_diversity(text3)

16.050197203298673

>>> lexical_diversity(text5)

7.4200461589185629

>>> percentage(4, 5)

80.0

>>> percentage(text4.count('a'), len(text4))

1.4643016433938312

>>>

To recap(扼要重述), we use or call(调用) a function such as lexical_diversity() by typing its name, followed by an open parenthesis, the name of the text, and then a close parenthesis. These parentheses will show up often; their role is to separate the name of a task—such as lexical_diversity()—from the data that the task is to be performed on—such as text3. The data value that we place in the parentheses when we call a function is an argument(实参) to the function.

You have already encountered several functions in this chapter, such as len(), set(), and sorted(). By convention, we will always add an empty pair of parentheses after a function name, as in len(), just to make clear that what we are talking about is a function rather than some other kind of Python expression. Functions are an important concept in programming, and we only mention them at the outset(开始) to give newcomers a sense of the power and creativity of programming. Don’t worry if you find it a bit confusing right now.

Later we’ll see how to use functions when tabulating(列表显示) data, as in Table 1-1. Each row of the table will involve the same computation but with different data, and we’ll do this repetitive work using a function.

Table 1-1. Lexical diversity of various genres in the Brown Corpus

|

Genre 风格 |

Tokens |

Types

|

Lexical diversity 词汇差异性 |

|

skill and hobbies |

82345 |

11935 |

6.9 |

|

Humor |

21695 |

5017 |

4.3 |

|

fiction: science |

14470 |

3233 |

4.5 |

|

press: reportage |

100554 |

14394 |

7.0 |

|

fiction: romance |

70022 |

8452 |

8.3 |

|

religion |

39399 |

6373 |

6.2 |

浙公网安备 33010602011771号

浙公网安备 33010602011771号