Python自然语言处理学习笔记(62):7.3 开发和评价分块器

7.3 Developing and Evaluating Chunkers 开发和评价分块器

Now you have a taste of what chunking does, but we haven't explained how to evaluate chunkers. As usual, this requires a suitably annotated corpus. We begin by looking at the mechanics of converting IOB format into an NLTK tree, then at how this is done on a larger scale using a chunked corpus. We will see how to score the accuracy of a chunker relative to a corpus, then look some more data-driven(数据驱动的) ways to search for NP chunks. Our focus throughout will be on expanding the coverage of a chunker.

Reading IOB Format and the CoNLL 2000 Corpus

读取IOB格式和CoNLL2000语料库

Using the corpora module we can load Wall Street Journal text that has been tagged then chunked using the IOB notation. The chunk categories provided in this corpus are NP, VP and PP. As we have seen, each sentence is represented using multiple lines, as shown below:

he PRP B-NP

accepted VBD B-VP

the DT B-NP

position NN I-NP

...

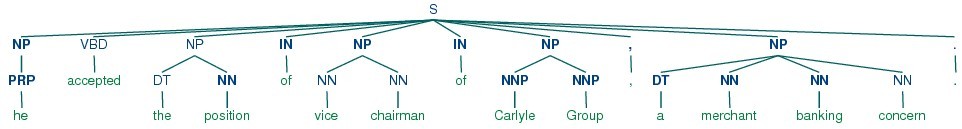

A conversion function chunk.conllstr2tree() builds a tree representation from one of these multi-line strings. Moreover, it permits us to choose any subset of the three chunk types to use, here just for NP chunks:

|

We can use the NLTK corpus module to access a larger amount of chunked text. The CoNLL 2000 corpus contains 270k words of Wall Street Journal text, divided into "train" and "test" portions, annotated with part-of-speech tags and chunk tags in the IOB format. We can access the data using nltk.corpus.conll2000. Here is an example that reads the 100th sentence of the "train" portion of the corpus:

|

As you can see, the CoNLL 2000 corpus contains three chunk types: NP chunks, which we have already seen; VP chunks such as has already delivered; and PP chunks such as because of. Since we are only interested in the NP chunks right now, we can use the chunk_types argument to select them:

|

Simple Evaluation and Baselines 简单的评价和基准

Now that we can access a chunked corpus, we can evaluate chunkers. We start off(开始) by establishing a baseline for the trivial(不重要的) chunk parser cp that creates no chunks:

|

The IOB tag accuracy indicates that more than a third of the words are tagged with O, i.e. not in an NP chunk. However, since our tagger did not find any chunks, its precision, recall, and f-measure are all zero. Now let's try a naive regular expression chunker that looks for tags beginning with letters that are characteristic of noun phrase tags (e.g. CD, DT, and JJ).

|

As you can see, this approach achieves decent(相当好的) results. However, we can improve on it by adopting a more data-driven approach, where we use the training corpus to find the chunk tag (I, O, or B) that is most likely for each part-of-speech tag. In other words, we can build a chunker using a unigram tagger (Section 5.4). But rather than trying to determine the correct part-of-speech tag for each word, we are trying to determine the correct chunk tag, given each word's part-of-speech tag.

In Example 7.8, we define the UnigramChunker class, which uses a unigram tagger to label sentences with chunk tags. Most of the code in this class is simply used to convert back and forth(反复地) between the chunk tree representation used by NLTK's ChunkParserI interface, and the IOB representation used by the embedded tagger. The class defines two methods: a constructor which is called when we build a new UnigramChunker; and the parse method which is used to chunk new sentences.

The constructor expects a list of training sentences, which will be in the form of chunk trees. It first converts training data to a form that suitable for training the tagger, using tree2conlltags to map each chunk tree to a list of word,tag,chunk triples. It then uses that converted training data to train a unigram tagger, and stores it in self.tagger for later use.

The parse method takes a tagged sentence as its input, and begins by extracting the part-of-speech tags from that sentence. It then tags the part-of-speech tags with IOB chunk tags, using the tagger self.tagger that was trained in the constructor. Next, it extracts the chunk tags, and combines them with the original sentence, to yield conlltags. Finally, it uses conlltags2tree to convert the result back into a chunk tree.

Now that we have UnigramChunker, we can train it using the CoNLL 2000 corpus, and test its resulting performance:

|

This chunker does reasonably well, achieving an overall f-measure score of 83%. Let's take a look at what it's learned, by using its unigram tagger to assign a tag to each of the part-of-speech tags that appear in the corpus:

|

It has discovered that most punctuation marks occur outside of NP chunks, with the exception of # and $, both of which are used as currency markers(货币标志.). It has also found that determiners (DT) and possessives (PRP$ and WP$) occur at the beginnings of NP chunks, while noun types (NN, NNP, NNPS, NNS) mostly occur inside of NP chunks.

Having built a unigram chunker, it is quite easy to build a bigram chunker: we simply change the class name to BigramChunker, and modify line in Example 7.8 to construct a BigramTagger rather than a UnigramTagger. The resulting chunker has slightly higher performance than the unigram chunker:

|

Training Classifier-Based Chunkers 训练基于分类器的分块器

Both the regular-expression based chunkers and the n-gram chunkers decide what chunks to create entirely based on part-of-speech tags. However, sometimes part-of-speech tags are insufficient to determine how a sentence should be chunked. For example, consider the following two statements:

| (3) |

|

|

These two sentences have the same part-of-speech tags, yet they are chunked differently. In the first sentence, the farmer and rice are separate chunks, while the corresponding material in the second sentence, the computer monitor, is a single chunk. Clearly, we need to make use of information about the content of the words, in addition to just their part-of-speech tags, if we wish to maximize chunking performance.

One way that we can incorporate(合并) information about the content of words is to use a classifier-based tagger to chunk the sentence. Like the n-gram chunker considered in the previous section, this classifier-based chunker will work by assigning IOB tags to the words in a sentence, and then converting those tags to chunks. For the classifier-based tagger itself, we will use the same approach that we used in Section 6.1 to build a part-of-speech tagger.

The basic code for the classifier-based NP chunker is shown in Example 7.9. It consists of two classes. The first class is almost identical(同样的)to the ConsecutivePosTagger class from Example 6.5. The only two differences are that it calls a different feature extractor and that it uses a MaxentClassifier rather than a NaiveBayesClassifier. The second class is basically a wrapper(包装器) around the tagger class that turns it into a chunker. During training, this second class maps the chunk trees in the training corpus into tag sequences; in the parse() method, it converts the tag sequence provided by the tagger back into a chunk tree.

| ||

The only piece left to fill in is the feature extractor. We begin by defining a simple feature extractor which just provides the part-of-speech tag of the current token. Using this feature extractor, our classifier-based chunker is very similar to the unigram chunker, as is reflected in its performance:

|

We can also add a feature for the previous part-of-speech tag. Adding this feature allows the classifier to model interactions between adjacent(邻近的) tags, and results in a chunker that is closely related to the bigram chunker.

|

Next, we'll try adding a feature for the current word, since we hypothesized that word content should be useful for chunking. We find that this feature does indeed improve the chunker's performance, by about 1.5 percentage points (which corresponds to about a 10% reduction in the error rate).

|